Carl Craig and the History of Movement

In 2000, Detroit's Hart Plaza vibrated with the sound of techno, house, and hip-hop for the first time during the inaugural Detroit Electronic Music Festival (DEMF). This was revolutionary, because at the time dance music was still very underground in the U.S. and there were few festivals centered on it. Ultra Music Festival, launched in 1999 and Cyberfest (a now-defunct San Francisco-based festival) were among the only other festivals catering to dance music fans.

DEMF morphed through various iterations under different organizers and names, eventually evolving into the Movement Music Festival we know and love today. When long-time local rave producer Paxahau took the reins in 2006. Ahead of Movement returning this weekend for the 21st edition of techno in the city that birthed techno, we chatted with techno pioneer and DEMF co-founder Carl Craig and Paxahau's founder Jason Huvaere about its storied and legendary history, and deep impact on the scene.

Craig, along with local event organizer Carol Marvin, moved mountains to successfully throw the inaugural DEMF, and the second one in 2001, both of which were free to attend. The first event almost didn't happen due to the city's delay on approving permits, but Craig's brother-in-law, who worked in the mayor's office for Detroit city cabinet member Lisa Webb Sharpe at the time, saved the day by getting him a meeting with her.

"I went in with my dad and convinced her what electronic music was because a lot of people that were older than me didn't understand it. Later on, she said to me, 'This festival has been really great because I have never seen soccer moms drive down and drop their kids in Downtown Detroit," he explains with a laugh.

It did all come together, and Craig convinced a stellar group of artists, many of them his friends and collaborators from the local scene to play the event. It brought the underground above ground, showing the city that their scene mattered, and also created connections within the wider Detroit community.

"It was something that was really exciting for me. When we announced that Slum Village and The Roots were playing, the hip-hop community got excited about this techno festival. That was amazing to see happen," Craig shares enthusiastically. "The majority of them that were approaching me about it were African American kids, that made it even more exciting because it was like I was touching the people that grew up like me and went to public school in Detroit. They probably had had similar experiences, good and bad. I felt that what was happening was that I was touching people with the music in a similar way that the Electrifying Mojo was on the radio in the '70s, '80s and '90s."

He explains that everyone in the scene at the time wanted a techno festival to happen in Hart Plaza because that's where Detroit's cultural events were held. Those events, which included things like the Greek-American festival and African world festival, "were always a big deal" to Craig when he was growing up. The free annual Detroit Jazz Festival launched in the plaza in 1980, which he calls "groundbreaking" for taking place there, and further inspired him and his fellow techno forefathers to bring their scene and sound to the outdoor city square. They were also inspired by the electronic festivals they'd been playing in Europe and Japan. "We thought, 'What about Detroit? What about the U.S.?' Being the D.I.Y. city that is Detroit, we're like 'We can do it!'"

The innovative Sonár festival in Barcelona especially served as creative inspiration for the Planet E founder. (Sonár began in 1994 and Craig had already played it a few times prior to 2000).

"Sonár was doing stuff that was different. It wasn't like they were trying to put on a concert. A lot of how we see the impact of videos with music, they were already pushing the boundaries with that in the '90s," he explains. "That had a big influence on me; [it was important to me]that my lineups and the festival itself is seen as being a high quality, sophisticated event, not just sticking some people together and saying 'Here's a festival.'"

In addition to placing his emerging underground scene in the sunlight and connecting it with the hip-hop community, he had his eye on artists who were doing things differently, not unlike himself. He explains he tried to do things people weren't doing that were really interesting. He booked a DJ that added power tools to electronic music (19 years before Flume!), someone that he saw as "taking music and the idea of what can be done with it another way."

It can't be underestimated how different things really were for dance music back then. Even now, deciding to throw a free three-day family friendly rave would be difficult, even with so many more DJs and ravers out in the world. The first DEMF was a turning point for dance music. "Doing a [dance music] fest in 2000 was like bringing the rave from illegal to legal," Craig muses.

"Electronic music wasn't really popular yet, it was in the shadow of the music business and still regularly referred to as underground music. So, having an event that would draw thousands of people during the day and then spread those people out across venues at night was pretty incredible. It was a justification to the electronic music community that we're being seen, we're going to be okay, we're evolving, and that felt great," Huvaere reflects.

"Now, things have changed a lot, where most touring electronic musicians are playing clubs, and most clubs now are owned by a corporation. We were still kind of rebellious [back then]; the nights would go really late and things were kind of early before a blueprint was made, and now it's definitely a different era for electronic popularity."

And the blueprint for throwing a stellar large-scale electronic music event was crafted by Craig with that groundbreaking first festival.

"[The first DEMF] set the mood for every techno event that's happened there 'til now. I was like the opening DJ setting the tone," Carl adds. And it was a success. "The main stage was what we wanted to see full, and it was every night. The first night The Roots, then Mos Def and DJ Gary Chandler, then Derrick [May] and Richie Hawtin closed out the stage. Kenny [Larkin], me and Stacey Pullen were crying and hugging each other."

That inaugural house and techno fest in Hart Plaza deeply impacted everyone involved, the city of Detroit, and the wider dance music scene. The blueprint helped put dance music on the map for a wider audience, and continues to be used to this day to honor and uphold its Black and underground roots. It is important and deeply impressive that Movement has stayed independent over the decades, as the rave industrial complex continues to morph the scene, pinching pennies from ravers as they white-wash the genres origins. It is a place for the next generation of ravers to learn about and experience the history of the music that moves them, a platform for artists, by artists, and a flame that keeps the rebellious energy of underground house and techno alive and well. Movement doesn't need to update its original blueprint much because it was revolutionary then, remains essential now, and the music and artists keep things fresh.

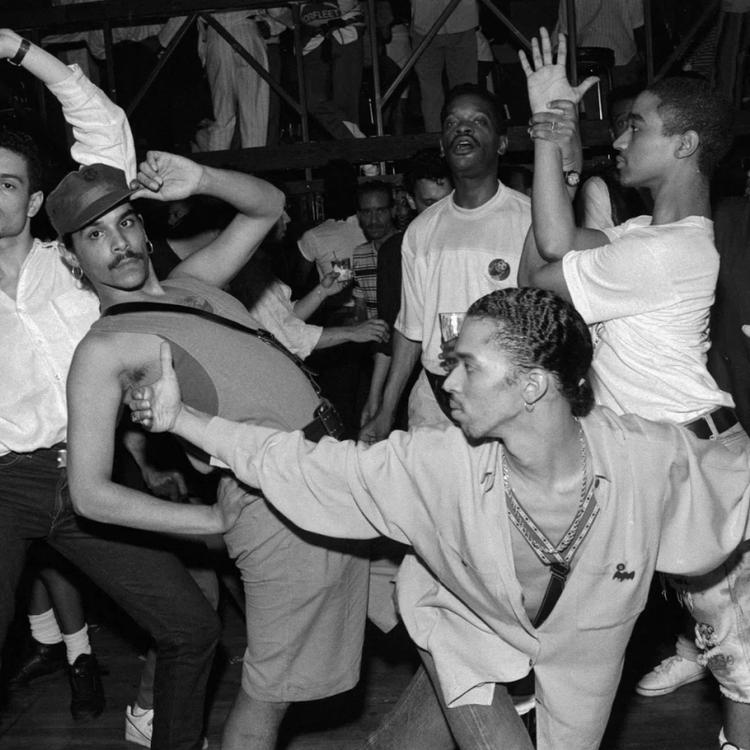

While it was still underground, the wider North American rave scene around the turn of the century, was definitely happening, as Craig explains. Dancers were reveling in Detroit, Chicago, New York, Miami, Los Angeles, New York, at gay clubs in Atlanta, and even in Milwaukee, Minneapolis and in literal cornfields. He notes that a lot of raves were happening in the Midwest, with Richie Hawtin responsible for many of them (before he got in trouble at the border), including a massive one in a cornfield outside of Windsor, Canada.

When asked what the state of dance music was like in North America around 2000, the Paxahau creator notes the direct impact the festival had on the scene from the start, and how amazing it was to see such a great turnout for an underground event. It was like a wider cast was finally coming to the house and techno party, literally and metaphorically.

"It was noticeable seeing the audience size and the budgets getting bigger, meaning a nicer venue, a nicer sound system. But myself, my co-workers and my friends, we'd loved this music for so long, we already knew it was amazing. So it was just more and more people catching it, in the right space at the right time. And the Detroit event has musically stayed pretty on course ever since then… [At Paxahau] we were always and still are focused on Detroit artists," Huvaere says.

At the 2005 event, then called Fuse-In and helmed by another Detroit techno forefather, Kevin Saunderson, Paxahau hosted the Underground stage. This was the first year tickets were sold—three-days for $25, $10 for single days—but the event saw a financial loss. Saunderson stepped down the following year, so Paxahau took over, changed the name to Movement and has run things ever since. Craig, Saunderson, and many of the fellow Detroit OGs, along with the Motor City next gen as they join the scene, continued to pop-up, have continued to play the fest and serve an important role in keeping things authentic to its roots.

"What was interesting about watching those documentaries about Fyre Festival is people don't realize how close every year is with doing a festival, that it could be your last or it could not even start. It's really touch and go unless you have a lot of financial backing. So with Paxahau, I think they've been a lot more aggressive with being able to get outside money in sponsorship and selling stages and that kind of stuff, which has helped them to flourish for long and better than any of the other behind the scenes of the [previous] festivals," Craig notes.

Movement continues to have a positive impact on Detroit and the artists proud to call it home, and both the festival and the creatives that keep the Detroit electronic scene alive and thriving play a key role in attracting visitors and positive attention to the city.

"Movement is a beacon of light [for Detroit]. It's a very inspirational place for established artists as well as artists that are aspiring to grow. It's a great homecoming for everybody that lives here as well," Huvaere says. "It's been huge for this town. We've been fortunate enough to see Detroit grow a lot over the last 20 years and being a part of that growth and being no small contributor to the vibrancy of the city makes us feel good at work."

He continues that one of his favorite parts of the fest has been seeing producers meet at the festival and then later collaborate together. He also notes that music technology people will use Movement like an IRL focus group, chatting with 50-plus artists a day about a new mixer their company is working on to take notes back to the team.

"I think Movement has helped the city of Detroit far more than it's given credit," Craig adds. "I think people in Detroit didn't expect [the initial impact] and it resonated far and wide."

Detroit remains a unique creative ecosystem for a multitude of reasons, including that its more affordable than other major U.S. cities like wallet-busters New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. But the intention that artists bring to their work, community, and collaborations also play a big role—on all accounts, it’s a very supportive scene where mentorship is abundant. Detroit has always had a resilient spirit, a citizenry that when left behind by the American automotive industry, found ways to support themselves and utilize abandoned spaces for art, community gardens and more.

"We have a really big artist community here, and so much talent here. It's been in Detroit this whole time. Most of our shows are for a local audience," Jason shares. "We're still an independent company. There's pressure to continue to uphold the legacy and bring in new artists, to uphold our values without corporations, to rep the roots of techno."

The afterparties and festivities surrounding the main event have always been an important part of Movement, and remain so to this day, bringing revenue and good vibes to venues and other businesses around the city. Paxahau has always produced Movement afterparties, and a variety of independent labels, party crews, and DJs have hosted legendary fetes over the years, like Craig's Detroit Love event, Saunderson's KMS Records showcases and Seth Troxler's Monday morning day raves at The Old Miami. Some are in clubs and others are in mixed-use spaces, highlighting that D.I.Y. ethos of the innovative, creative city that constantly evolves itself.

Just as the festival and city have changed since 2000, the clubs have as well. According to Craig, the club scene was previously much stronger. Back in the day, some of the popular rave spots were Motor, The Shelter at Saint Andrew's Hall (now owned by Live Nation), 1315 Broadway, Cheeks, UBQs, and the Music Institute.

"The most important club was the Music Institute. It was very short lived, I think it was only around for about three years or something. That one had the impact that was needed in Detroit," Carl reflects. "Some of the most beautiful moments I experienced were there."

One of the most heart-warming things about Movement is how family friendly and inclusive the event feels. This stood out to me when I attended in 2019. I saw a young kid break dancing to techno while his parents and others circled around him cheered him on. Techno Grandma, who rolls around in an electric wheelchair with a big smile is a staple of the event. I wondered if maybe this was Midwestern hospitality and/or the fact that people were really there for the music that fostered such a friendly, respectful crowd. Craig asserts that it is specifically "the vibe and legacy of Hart Plaza," where many family friendly community events are held, that keeps things so wholesome.

Thankfully, Paxahau made it through pandemic thanks to their Twitch partnership and the work of their legal team. "18 months without live events was decimating," Huvaere reflects. As dance music continues to become increasingly corporate in this country, independent rave organizers and dance fests feel extra essential to keep the spirit of its rebellious, inclusive roots alive. And since they've been able to return to programming events in Detroit, they will keep doing so as long as it feels right. Both he and Craig see Movement continuing into the future, God willing.

"We're not Vegas or Miami or L.A., we're different and that’s okay. As long as we stay relevant and people keep coming, we'll keep doing Movement," Huvaere concludes. "As long as they keep rolling like this, I don't see why Movement wouldn’t happen. But you never know…" Craig says.