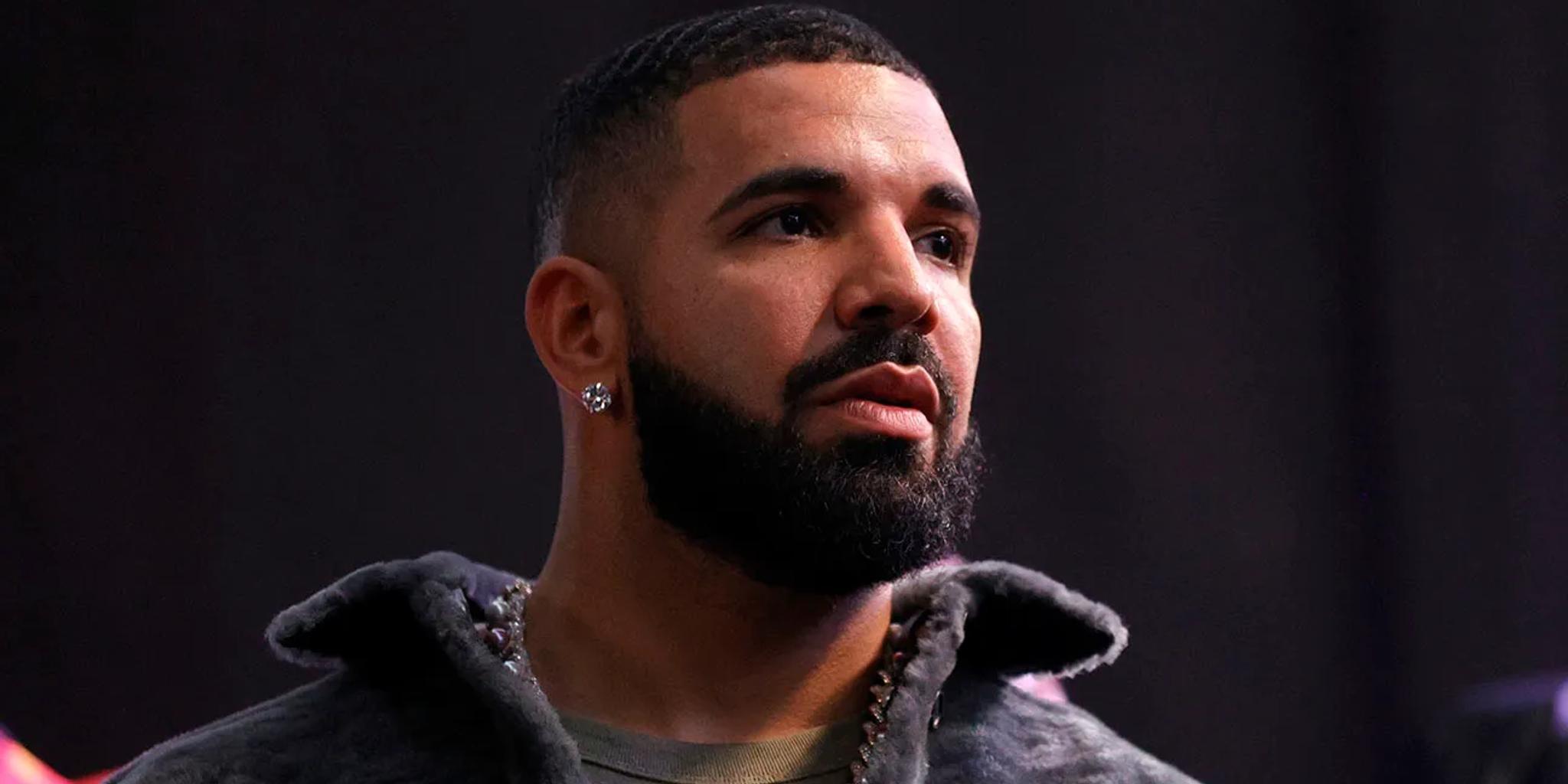

Drake's Detour in Dance Music is Disappointing

Drake has been incorporating dance music into his records since summer sixteen, a time when gas prices were low, Trump hadn’t been elected yet, and you couldn’t go anywhere without hearing “One Dance” or “Controlla.” While he had always poked fun at his singing rapper reputation, the release of Views marked the moment he fully embraced it. Despite how side-eye-inducing his faux patois was, Drake’s coquetry with dancehall and afrobeat was too catchy to not eventually grow on you.

Honestly, Nevermind dropped right as I got home from a dance music awards ceremony. So you can imagine my skepticism when people dubbed it a “house album.” It might be - in the same way, Aminé’s TWOPOINTFIVE is a drum n bass album, or PinkPantheress’ to hell with it is a jungle album - which they are, a little, I guess?

Sprinkled throughout the credits of this record are a plethora of electronic music producers. Most prominently, Drake enlists the help of South African 2022 Grammy Award-winning Black Coffee as one of the album’s executive producers and EDM trap trailblazer Carnage, who has since fully rebranded to his house alias, Gordo. High-profile house acts like these (and Frankie Knuckles is probably rolling in his grave at me implying Carnage is a house act) should mean that this album has the best dance music production. However, I skimmed the first few songs of the record, wondering where the actual dance music was.

Maybe I’m biased because Drake’s signature falsetto is deeply ingrained in my brain as synonymous with pop. Or maybe it’s because I’ve been listening to Drake bootlegs by some of the greatest electronic acts from both the underground and the mainstream for over ten years.

There’s a snake-eating-its-tail quality to the project, as Drake is probably the most well-loved, most remixed artist in dance music, but he’s especially spun by artists in US-based EDM. You can’t go to a club or festival set without hearing Drake. The Canadian rapper collaborating with these producers is a win for the scene in general. Still, I can’t help but expect more from someone who clearly pays attention to everything said about himself on the internet.

The first song that really caught my attention was “Currents,” produced by both Black Coffee and Gordo. The identifying bed squeaks, “what?” samples and bouncy drum pattern let listeners know exactly where the influence was coming from right away, yet it feels like baby’s first Jersey Club track. Plus, with the rise of east coast club music’s prominence on apps like TikTok, it comes across as pandering to not have an actual Jersey Club producer on the track.

I might have felt differently if the song was good, like Baltimore Club-injected “Sticky.” With credits from Gordo and RY X, “Sticky” grips listeners with its intoxicating pulsating percussion and echoing chopped-up-vocals that serve as the backdrop for Drake’s verses that honor club music’s raunchy lyricism. “Sticky” is proof you can make an interesting song that introduces rap listeners to dance music while also staying true to Drake’s sound.

From “Sticky” on, Drake and his producers attempt to get more experimental. If the first half of Honestly, Nevermind was to prepare longtime Drake fans for how much house they would hear on the record, they accomplished their mission, but not without boring people who already listen to house consistently. His dilettante’s approach to house music is unfortunately predictable. Gordo, acting as the beatmaker with the most production credits on the album, showcases how Drake is still a visitor in this space. Like another accent to try on or trend to hop, he’s secured one of the least relevant and respected names in dance music by those who follow anything other than cookie-cutter EDM. In the back half, we see more of Drake’s frequent collaborators like Kid Masterpiece and Noah “40” Shebib. Ironically enough, they help produce two of the album’s better house tracks, “Flight’s Booked” and “Overdrive.”

With hip-hop and electronic music producers using the same tools to create, Honestly, Nevermind proves that the divide between the two sample-based genres isn’t as significant as we think. And although there are drastic opposing views between people’s first impressions of the album, historically, Drake’s music stands the test of time among his stans and die-hards, regardless of how people react off rip.

I can also appreciate that Drake included so many electronic music producers on the record. Rampa, &ME, Alex Lustig, and Klahr have their catalogs full of dance music gems to dig through.

The day before the album dropped, Gordo tweeted, “This is about to be one of the biggest moments in dance music history…” For the first time, he wasn’t lying. The symbiotic relationship between hip-hop and house music has always been apparent to those who listen to both. House DJs have been blending rap in their mixes since the late ‘80s, when “Hip House” was an actual genre that existed (and was frequently clowned). Similarly, and in more recent years, rappers like Azealia Banks have been using house beats for at least a decade. But with Drake’s star power, this record is the opportunity that dance music can seize to finally get the reverence it deserves from the greater, “mainstream” music industry.

Is the album as a whole great? No. While there are songs I’ve run back a few times since my complete listen-throughs, Drake’s lyrical content here doesn’t even meet the low bar he’s set, perhaps a byproduct of an adjusted approach for blended house rap. Alternately, the beats will not satisfy most house music listeners either. So, this homogeneity and worst of both worlds quality begs the questions: why does this album exist, and who is this album actually for?