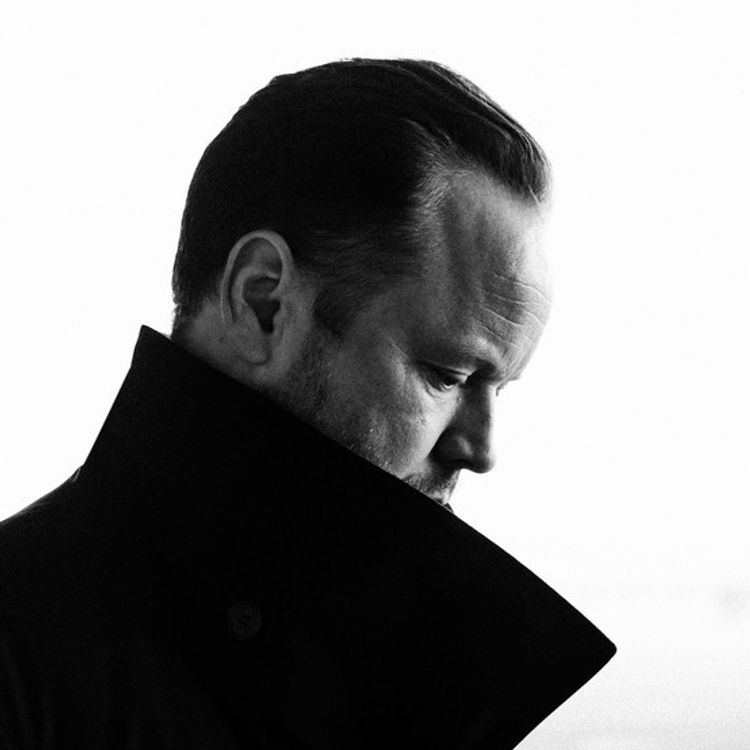

Artist Spotlight

Thomas Schumacher has weathered almost four decades of changes in electronic music since he first discovered it as a youth. These days the longstanding techno DJ and producer has the relaxed confidence of knowing that neither he, nor the music he loves, is going anywhere.

This calmness is a characteristic Schumacher shares with his fellow OCs or “original creators” in the techno genre, which, in the early days of electronic dance music, burned up the dancefloors and came with reverential respect for its producers and DJs. The genre fell out of favor for a spell, but its creators and followers carried on doing what they were doing—Schumacher being one of them. Then, another shift occurred, and techno became the coolest of electronic dance music genres, a position it continues to occupy.

“It’s still a wild roller coaster,” says Schumacher speaking from his home in Berlin, the techno capital of the globe. “When we started out, it was just techno. Throughout the ’90s, these sub genres happened, and people got confused. Techno was not the hot thing anymore. Same thing being a DJ. I went through times when people looked down on me, then they looked up to me. But now, I feel like techno is fully established. It has become this amazing canvas for people to project onto. If you ask people, what is techno to you, you will get ten different answers from ten different people. It’s something rather cool people want to identify with.”

Schumacher recognized cool as soon as he heard Depeche Mode’s 1983 album, Construction Time Again, which was recommended to him by a clerk in a record store in his hometown of Bremen, Germany. Construction Time Again was the gateway drug, as it were, for Schumacher’s discovery of new music. He soon found himself returning to synth-rich and drum machine-heavy tracks. Then, in the same record store where he discovered Depeche Mode, the clerk handed him his first acid house 12”, and Schumacher was ready to make music.

He got an afterschool job and saved to purchase costly equipment. Once again, a clerk, this time in the music store, guided Schumacher in the right direction.

“Everything was expensive,” Schumacher says. “Gathering information took so much time. Even simple things, like how to connect your gear, were really complicated. It took me years to find the right person to teach me. On the other hand, the benefit is you learn the trade properly. These days, everything is immediately available. It’s too easy. Too much information, too many choices, and people are overwhelmed. Then, everything was more difficult and took more time, but I think it gave me the chance to learn things from scratch.”

It was a natural step for Schumacher to start DJing to test out the music he was making. Once again, it was the clerk in the music store that helped Schumacher buy the correct—albeit very low-quality—turntables.

“They were not made for DJs,” recalls Schumacher. “It was so difficult, and it took me so much longer, but it also forced me to become really good at it. After two years, I mastered beat matching with these shitty turntables. The first time in a club when I had the proper Technics, it was super easy for me. “

Thomas Schumacher Press Pic 1993

Schumacher and a friend approached the promoter of the local house club about DJing, who strongly rebuffed them for wanting to bring techno to the venue. So they started their own party and quickly scaled up.

A year later, the same promoter who turned Schumacher away courted him to become a resident at his club. Here Schumacher learned the craft of DJing by playing six to eight-hour sets. And if he messed up, he heard about it. “The guy that ran the club was super-controlling,” Schumacher recalls. “He worked behind the bar and had a remote control for the sound system. When we messed up a DJ transition, he would mute the sound system and yell at us. It was so embarrassing.

“He was quite strict,” he continues. “No drugs while you’re working but also no alcohol. You can drink a beer every now and then, but no shots. Compared to these days, it was a completely different mindset. He could be a pain in the ass but at same time, he forced us to focus and helped me to hone my skills. I give him credit for that.”

Schumacher witnessed the music he was involved with going from obscure to mainstream over a few short years. “The last two or three Love Parades in Germany had over a million people,” he says. “I played on one of the trucks. We had come from super underground events with 150 people in a little cellar somewhere to this, and I’m an integral part of the scene. It filled me with a profound sense of pride.”

When Schumacher released his first productions on independent German labels, he says it “Gave me such confidence. I remember holding my music pressed on vinyl in my hands, making me a legit producer.”

In 1997 his track “When I Rock” debuted on Manchester’s very credible Bush Records. Carl Cox picked up on it, played it on his BBC Radio show, and according to Schumacher, “He just kept playing it, and I believe he singlehandedly broke the record, and it became this worldwide hit.” This leveled up Schumacher’s career from local DJ to internationally recognized name.

“When I was traveling, I realized a lot of people connect techno with Germany—even though it is a global phenomenon,” says Schumacher. “I was invited by the Goethe Institute, which represents German culture, to Mexico to talk about techno music and there were 1000 people in the auditorium. These moments feel great. Not that I need official recognition, but when you receive it, it is beautiful. It also gives you this reassurance that techno is not going to go away.”

While techno is global, Schumacher’s record labels tend to be location-specific. His first label, Spiel-Zeug Schallplatten was Bremen-based, and his second label Electric Ballroom is Berlin-bound. In between, Schumacher released music on Get Physical, Noir Music, Drumcode, Superstar Records, among others, including a stint as a major label artist, an experience he is not keen to revisit. Schumacher’s output has leaned toward singles, but he has put out his fair share of albums, although he may not do so again.

“Doing albums gave me a chance to show all sides of myself as a producer,” says Schumacher. “But every time I did an album, I felt like I was forcing myself to do it. I was told that’s how you have to do it. I think it was true for a long time. But then I also realized, it doesn’t mean I have to do it like that. The album format was designed for singers, for storytelling, to give them a chance to connect with the audience. Nothing like that applies to what I’m doing. It’s not the key to a successful career. I’m not going to rule out that I’m never going to do an album again, but for now, I’m happy to do singles.”

Schumacher’s longevity links to two key factors. His recognition of changing parameters and adaptability to those changes—without compromising his artistic vision or creative direction.

“For us, ‘OCs,’ as you say, the danger is to get bitter,” he observes. “I see, way too often unfortunately, old school producer/DJs ranting on social media, and it breaks my heart. It will not help you with your career or your feelings of not being respected enough. Times are always changing. Techno is ever changing. But it is so established and it’s rather positive and it’s not going to go away because it represents so much more.”