Why Music Moves the Human Brain — Explained by Michael Spitzer

Music isn’t just something humans invented for pleasure — it’s woven into who we are. In a Big Think video, musicologist Michael Spitzer, professor of music at the University of Liverpool and author of The Musical Human, unpacks why music has been part of us for millions of years and how it molds the brain, body, and our emotional lives.

Spitzer — who leads Liverpool’s department of classical music and is known for his work on Beethoven, aesthetics, and music and emotion — frames music not as a cultural add-on, but as something that emerged from our earliest movements as a species. “Humans have been making and learning to recognize music from the moment our species learned to walk on two legs,” he says. Walking gave early humans a predictable beat, and with it, a sense of time and pattern that still underlies how we experience rhythm today.

Music and Mental Health Go Hand in Hand

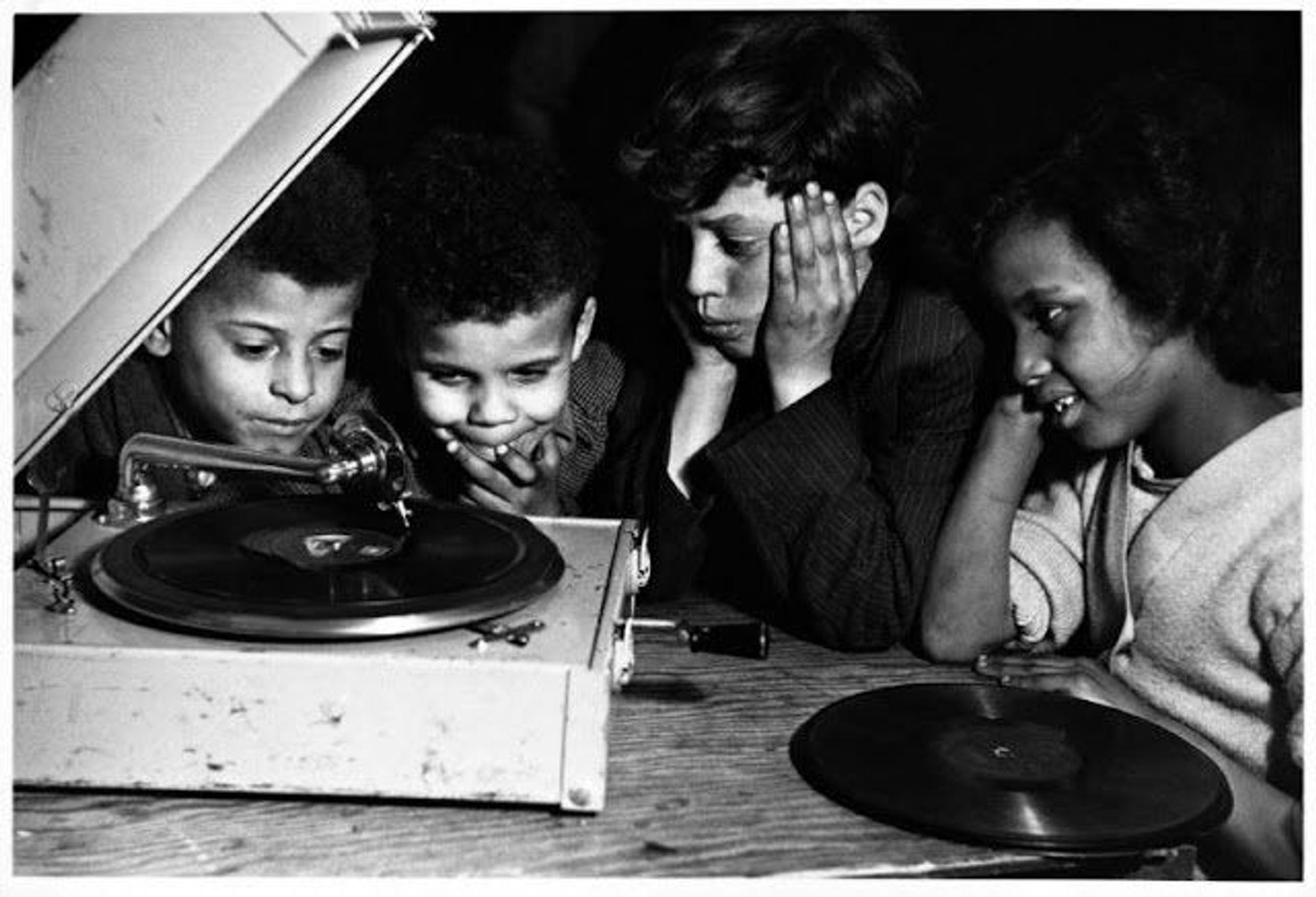

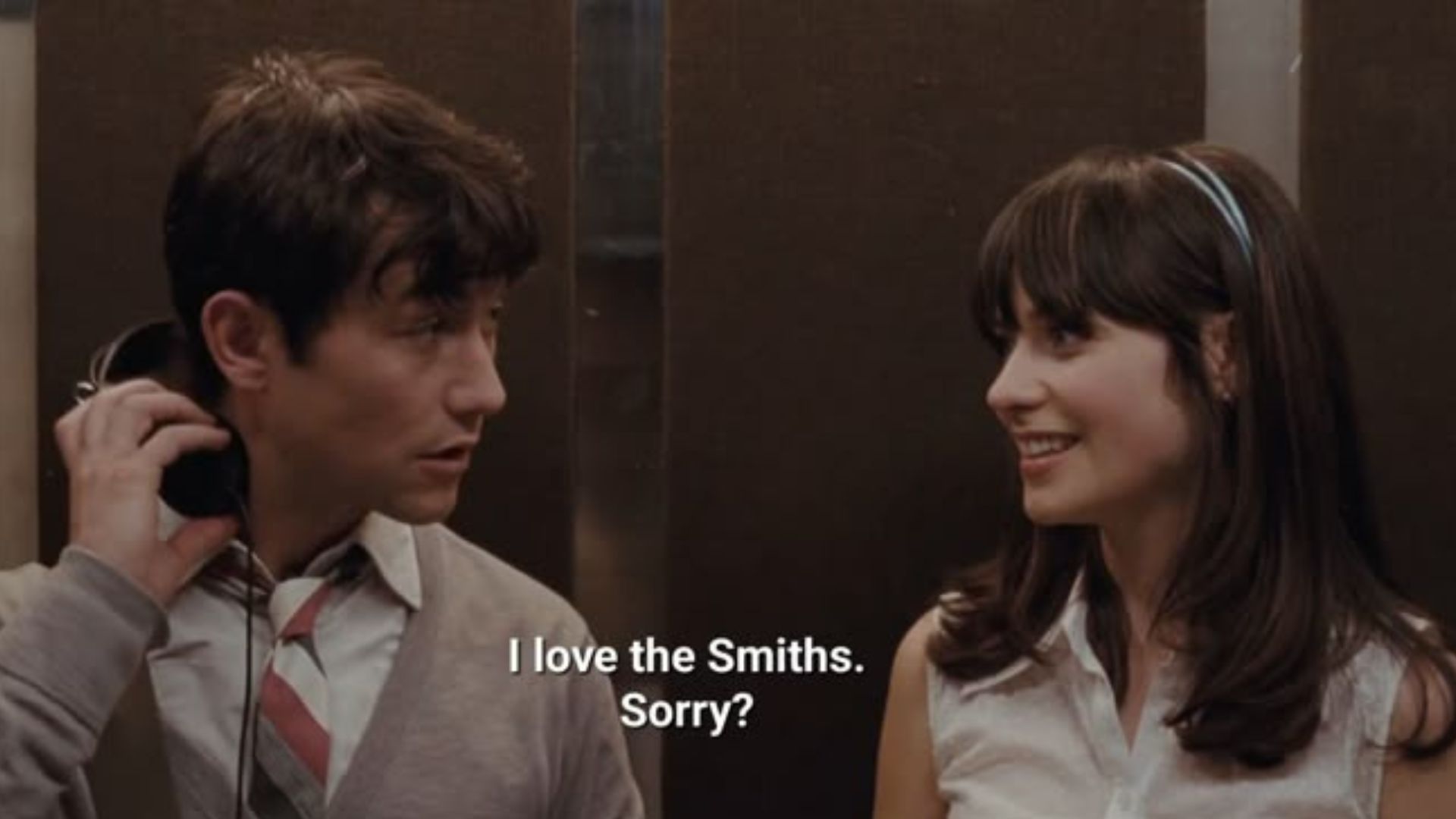

One of Spitzer’s strongest points is that music isn’t just entertainment — it’s a tool for survival and mental well-being. “The biggest draw to mental health is loneliness,” he says. “Music can bring people together. You don’t have to actively make music with somebody else — just to listen to music plugs you into a social network, because every notion of music is social. It’s formed of social conventions.”

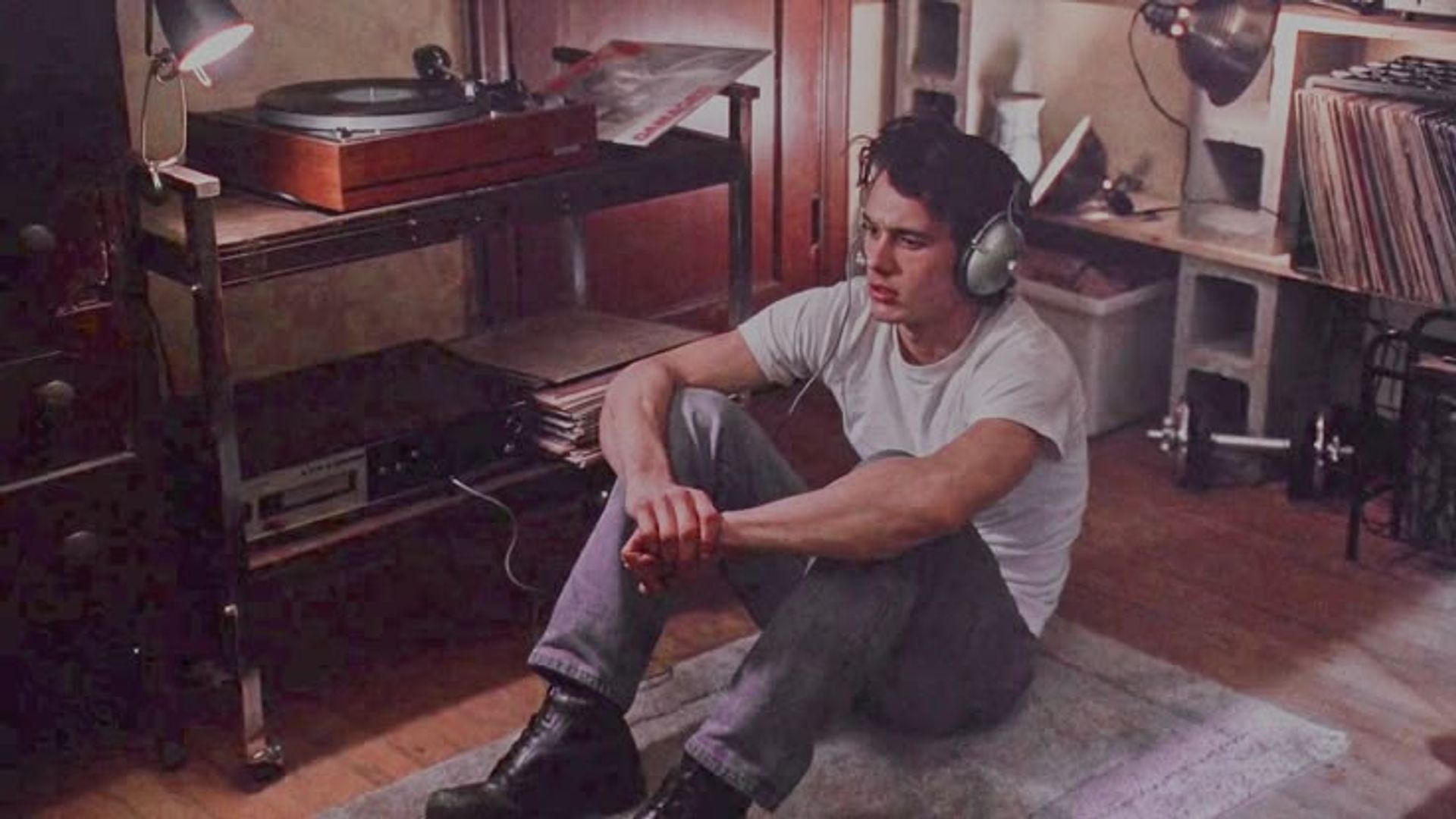

Listening doesn’t just connect you to others; it also has measurable effects on the body. “Music lowers stress by reducing cortisol,” Spitzer explains. “It gives you pleasure, makes you happy by flooding the brain with neurotransmitters like dopamine.” He adds that music helps tag memories, express identity, and process feelings “too precise for words.”

Interestingly, Spitzer warns against thinking of music as mere relaxation: “The word relaxation gives a sense of passivity, whereas to listen is a very active and creative activity.” True listening, he suggests, is closer to mindfulness — an act of deep engagement rather than background noise.

Why Rhythm and Emotion Feel So Instinctive

Humans are wired to imitate and feel what we hear. Spitzer points to mirror neurons — brain cells that fire when we see or hear an action. “When the brain sees an action, you don’t have to move to experience that motion in your brain,” he says. “Mirror neurons are responding sympathetically. We’ve always had an instinctive faculty to imitate. We call it mimesis.”

That explains why yawns are contagious — and why emotions in music are, too. “When I hear a sad song, my body, my mirror neurons, are instinctively sympathizing, are mirroring the sadness of the song,” Spitzer says. Not only does music represent feelings, it also physically pulls us into them.

He also connects this to the way emotions evolved for survival. Happiness signals reaching a goal. Anger appears when a goal is blocked. Sadness follows loss. Fear prepares us to freeze, fight, or flee. Music taps directly into these circuits, which is why some songs hit so hard they cause chills — or frisson.

“There are moments in music which are so intense… you have the same parts of the brain which respond to that as respond to fear,” Spitzer explains. That’s why goosebumps rise when a song suddenly swells — it’s fear’s wiring, but in a safe space.

The Brain’s Music Network

Underneath these emotional responses is a fascinating neural map. Spitzer notes that the brainstem — our most ancient layer — reacts reflexively to sudden sounds, while the basal ganglia judge whether what we’re hearing feels pleasant or unpleasant. The amygdala handles core emotions like fear, sadness, anger, and happiness.

At the top, the neocortex processes patterns and complexity — the reason we can appreciate a fugue, follow a jazz solo, or predict a beat drop. Together, these regions show why music reaches us at every level: from instinct and survival to intellectual and emotional depth.

Spitzer’s video is a reminder that music is a part of our biology and psychology. From the first hominin footsteps to today’s streaming playlists, music has been a way for humans to connect — to each other, to memory, and to emotion itself.

For anyone who’s ever felt a song lift their mood, bring back a vivid memory, or cause goosebumps out of nowhere, Spitzer’s insights explain why: music is movement, memory, and meaning combined. It’s not simply entertainment — it’s something deeply human.