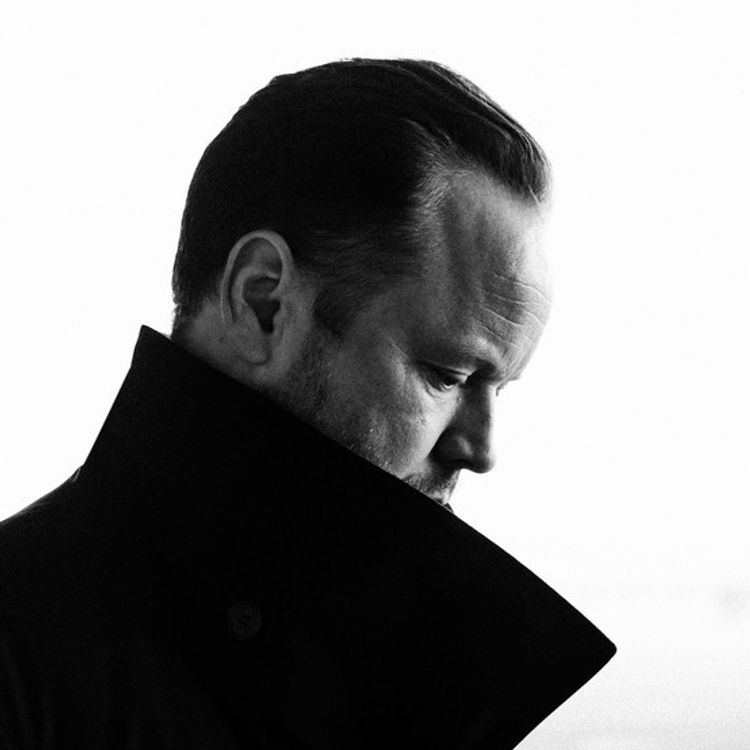

Artist Spotlight

UK-born-and-bred house music veteran Low Steppa, née Will Bailey, has a career peppered with aliases, accolades, and career highs that include being at the axis of tectonic shifts in dance music several times over. He’s one of the select few to hold the title of Defected Records resident. And his label, Simma Black, has established itself as a tastemaker, releasing records that hold steadfast to his ethos that “music’s got to have a groove. It’s got to have a bit of soul.” His solo releases follow suit, walking the line between blissfully dusty classics and pristinely executed modern groovers. In a scene obsessed with trends, Low Steppa remains fascinated with what forms the backbone of dance music.

“I think when you’re younger, you’re more prone to gravitate towards fads that aren’t your thing,” he explains about the decade preceding his 2013 debut of the Low Steppa alias. Bailey spent his early career shifting through various sounds that helped pave the way for dance music’s inevitable explosion in the mid-aughts. Among them were his genre-bending work as part of fidget house outlet Twoker (with Alex Calver aka Skapes) and eponymous, genre-spanning work that saw him collaborate with a range of artists from Chris Lorenzo and Gettoblaster’s Paul Anthony to Valentino Khan.

For an artist whose entrée into dance music was on the soulful house tip, it became increasingly clear that the further he drifted from his roots, the less authentic his music felt.

A sense of nostalgia is inherent in even the most current sounds of “classic” house music. Those that have found inspiration in the creators of the culture, like Masters At Work, Todd Terry, and Frankie Knuckles, are recontextualizing a timeless aesthetic that has continued to persist on the dancefloor for nearly 40 years.

“That’s the beautiful thing about real house music,” he explains wistfully. “You’ve got all the things that are going on right now, you know, your tech house, all this, but it all sort of comes and goes away. Whereas your classic, sort of Defected vibe, I believe it’s always gonna be there. It’s like the backbone to a lot of things. So, I feel like I’ve drifted around along on back to what I wanted to do when I first started DJing and buying vinyl.”

He explains that, unlike other artists who were brought up on a diet of soul and disco, the Bailey household was one rife with rock and pop music. His dad, Richard Bailey, spent a spell as the keyboardist for '80s metal band Whitesnake. And he remembers growing up around studios in Birmingham, England.

“But I kind of made my own way through his record collection. I was obsessed with ‘Thriller’ when I was a kid. And so I think that got me on my way.”

In the ’80s and ’90s, he grew up parallel to the storied UK rave scene. And in Birmingham, a city associated with the tougher side of dance music (and the home of bassline house), he first discovered D&B. By the time he was getting into club life, he found the soulful side of house via BBC Radio 1 DJ Danny Rampling’s Love Groove Dance Party show.

He’d happened upon a sound that often appeals to a more seasoned dance music aficionado. As the years drifted on and he wound his way through a vast sonic soundscape, the distinct syncopated drums of the Birmingham Sound and timeless vibe of soulful house never left him. So when he released his garage-inspired rework of Route 94 and Jess Glynne’s “My Love” as a free download in 2013, he’d finally returned to the sound that made him fall in love with house music.

“I’ve always loved those skippy beats,” he explains about the bootleg that eventually made its way into Route 94’s DJ sets. “And it’s just fun when you’re making beats [thinking] ‘just where can I put these snares?’ And ‘what groove am I gonna get an average swing or quantized one off my beats?’”

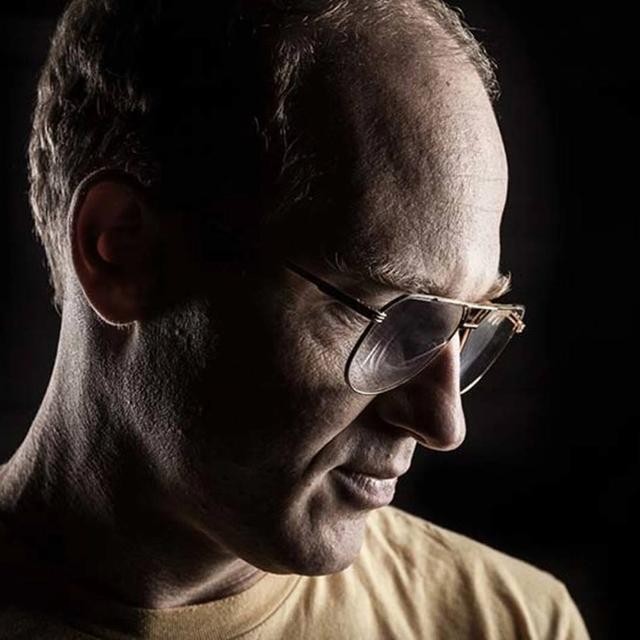

As he gives a window into the process behind creating one of his impossibly danceable grooves, he recalls the wise words of Grant Nelson, also known as Wishdokta, Bump & Flex, and N’n’G, who is heralded as the “godfather of UK garage.”

“I think it was Grant Nelson that said to me once, ‘you know you’ve got to be grooving off just your drums.’ And that’s the approach I always have. I mean look at the drum beats that bookend Kenny Dope - 'The Bomb,' stuff like that. You don’t really get so much anymore where a record has an amazing drum beat.”

While modern production techniques have allowed for music to be far cheaper and easier to produce, the reliance on machines and sample packs has created a space where the humanity of music has been somewhat lost. Low Steppa has spent his career trying to reclaim it. And when he hooked up with Defected, he found a group of like-minded folks seeking to do the same.

In 2016 he released Low Steppa’s Disco Party, a 66-minute throwback to the music that arguably made house possible. Defected founder Simon Dunmore recognized Bailey’s inherent need to understand the roots of the music he loved in his track selection. Dunmore hit Low Steppa up to say he’d spent all weekend listening to the mix.

“I think he sort of realized that I knew my music and I think that was one of the key things. I think Simon [has] got a lot of respect for people who know their music or the background of it.”

Bailey has long been a veracious sample hound and music historian. “And that I mean, that’s very important to him, I think. Because obviously, there’s not really people that know much more about it than him.”

After a few opening slots in the UK, Bailey was brought into the Defected fold. He’s released several dozen records there, including a throbbing, organ-laden remix of Hardrive’s “Deep Inside,” an impossibly funky rework of “Freedom” by CeCe Rogers and Jack Back aka David Guetta, and 2019’s disco-tinged “You’re My Life” that masterfully samples Jackie Moore’s 1979 “This Time Baby.”

And while he was already a well-established touring DJ, Defected also allowed him to spread the gospel of house music even further by being a staple on their global club and festival lineups.

“I think Defected did really help me get into the space I wanted to be in because it allowed me to go back to my roots and do what I really wanted to do,” Bailey says.

While he’s in the most creatively fulfilling space of his life, there are times when he feels he could take it even further. “I still can’t always play what I really want to. Sometimes I’d love to play a more soulful set, but when you’re in a festival or busy club [and] it’s hyping, you just know what you got to do. I do miss playing in a bar where people are just chilling, and you’re just playing some light, soulfuric vibes.”

The pandemic allowed him to connect even more with his roots by doing just that. He quickly became a staple of the streams and dug in the crates for long-lost house music gems. It’s likely what led to his monthly Defected Broadcasting House Show.

“I think that’s what was great about it for me. I went and found all these records I used to play. And I was just playing a lot of this old stuff and I loved it. Everyone was just at home and [the] dance floor was equal. Just play whatever you wanted, that was one of the beautiful views of it all for me during those times, as weird as it was.”

Low Steppa has had the good fortune of an extended and fruitful career in dance music. He’s remained a relevant and culturally significant voice for the duration. He explains that he’s done so by staying in his own lane.

“That’s exactly the phrase, stay in your own lane, and just be happy with what you’re doing," he says. "I’ve got my followers, and it’s important to just keep them happy, and not get to get caught up in the trends. I don’t really want to want to follow the trends. I mean, it’s great to hear stuff that’s new, and you’re like, 'oh, wicked,' and they get a vibe off that. But I do want to stick to what I’m doing.”