From Detroit to Berlin: How Techno Took Over the World

Techno has many beginnings, but let's start with the most obvious one: Kraftwerk. The German synth-pop inventors' 70s and 80s albums had an immeasurable impact, but we can certainly point to their lineage in Detroit. Techno's inventors all worshiped Kraftwerk, to the point that when the group played the Motor City in 1998, one producer thanked them for his career.

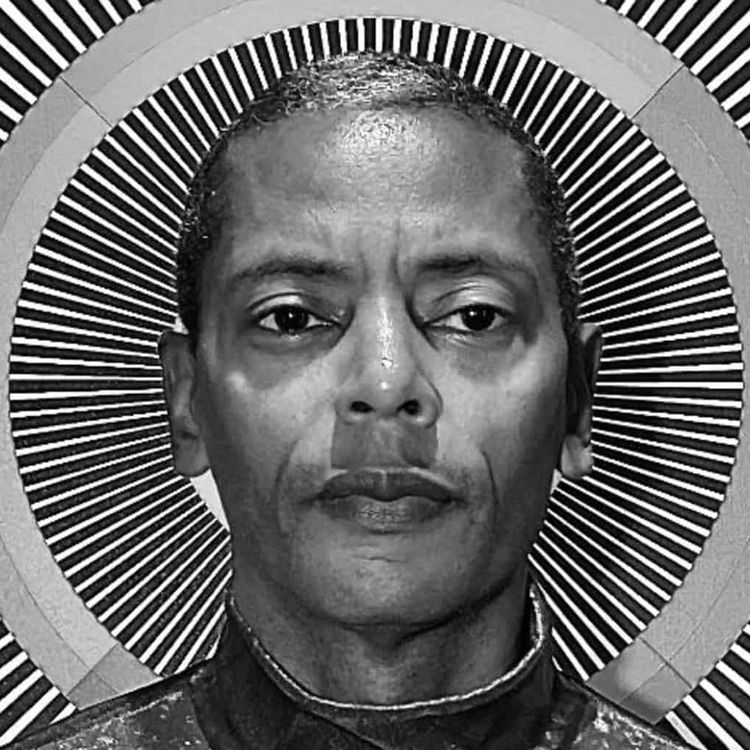

"I've always called my music techno, from day one," Juan Atkins once said. "Even with Cybotron, we called that techno." And if any one person invented techno, it's Atkins, whose first project, Cybotron, a duo with Rik Davies, was classed as electro in the early eighties. But that would change in 1988, with the release of Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit, featuring Model 500's "Techno Music"—another Atkins alias.

"The working title was The House Sound of Detroit," Atkins said in 2012. "I submitted my track—it was one of the last tracks submitted—called 'Techno Music.' Most of the artists on the album [said], 'We learned our craft from Juan Atkins.' Well, how can we call this house music? So, they changed the title."

This music was defiantly futuristic. "The future is really the most open-ended subject you can have," Atkins said in 1997. "It can be whatever you want it to be. You're not confined to any kind of parameter."

But techno was, and is, also in constant conversation with its antecedents. The electric jazz and fusion of Miles Davis and Herbie Hancock are key touchstones. Detroit's Underground Resistance titled a key 1992 track "Jupiter Jazz." And Carl Craig (also from Detroit—sense a pattern?) created the Innerzone Orchestra's Programmed (1999), an album steeped in Hancock's pre-Head Hunters work on Sextant.

Once techno left Detroit, it spread fast. In 1989, New Yorker Frankie Bones' track "Call It Techno" caught the spirit: "Computer noise and pounding bass/Hits you in the face/Like a hammer." But the New York techno records that turned heads belonged to Queens-bred Joey Beltram.

His Volume 1 EP, in 1990, featured the landmark "Energy Flash." Even more explosive was 1991’s “Mentasm,” by Second Phase, a.k.a. Beltram and Mundo Muzique (born Mike Mundo). For a while, nearly everyone who made techno worked audible variations on the "Hoover" noise at "Mentasm's" center. "People were making different sounds by fucking with the waveform and the attacks on it," says Adam X.

Techno's real home overseas was Berlin. Tresor, the club and label, booked and released numerous Motor City producers, from Atkins to Blake Baxter to Jeff Mills. "You felt this alliance," Tresor founder Dimitri Hegemann said in 2002. "Tresor was the first to invite Detroit DJs to Berlin and bring techno to Europe. They helped develop the music a lot. They really influenced it. but we also assisted them, we gave them a space."

Berlin became a mecca for techno—and in the early 2000s, it became its de facto home, particularly as numerous American DJs and producers moved there in the wake of the era's rave crackdown. In 2002, one DJ told The Wire, "There's too many DJs in Berlin."

Tresor Night Club in Berlin

The sound du jour in Berlin during the mid-2000s was minimal techno—pioneered by Robert Hood and Daniel Bell in the 90s, both from, you guessed it, Detroit. Hood is a former member of Underground Resistance. But Berlin plays a decisive role there, too, thanks to Basic Channel's run of mysterious, hazy, and entropic 12-inches from the 90s, among others. But the 2000s' minimalism, while often artful and cunning—see the Perlon catalog—was also widely criticized for being too intellectual and arty, missing the music's sweaty essence.

In some ways, it resembled a thumping variation on IDM—or "intelligent dance music," the unfortunately named listening-first style. The term comes from the two Artificial Intelligence compilations that Warp Records issued in the mid-90s. Their lineups tell the tale: Aphex Twin, Autechre, Dr. Alex Paterson (the Orb's leader), Speedy J. The music wasn't intended for dancing, per se.

"I prefer it when people stand around," Richard James, a.k.a. Aphex Twin, told Spin in the mid-90s. "It's amusing hearing what tracks people like shagging to, but I don't care what people think."

Thankfully, most techno artists do want people to move. In the 2010s, the big move has been to emphasize the industrial/EBM (electronic body music, a la Front 242) side of techno, which is sizable—Jeff Mills played in the industrial group Final Cut before moving into techno full time. DJs like Helena Hauff and Nene H have been playing some of the most blistering sets around by commingling two kinds of hard, dark music together. Far from simple or limited, techno has proven a widely varied and variable template.