Industry Spotlight: Danny Whittle

Danny Whittle’s phone starts ringing the minute he sits down to speak with Gray Area over video chat. “The life of a promoter,” he laughs before picking up to tell them he’ll call back.

The interruption elicits little reaction from Danny. At various other points throughout his nearly three-decade career, though, he’s received calls that set him on a course through key moments in dance music history.

Ibiza is gearing up for its busy season. Danny knows better than most that the hustle and bustle come with the territory this time of year. Since his first visit to the White Isle in 1996, he’s played key roles in such storied brands as Renaissance, Ministry Of Sound, Home, Pacha, and International Music Summit. Danny has made a career of sizing up dance floors and figuring out how to turn them into profit machines. His judgment is seldom wrong.

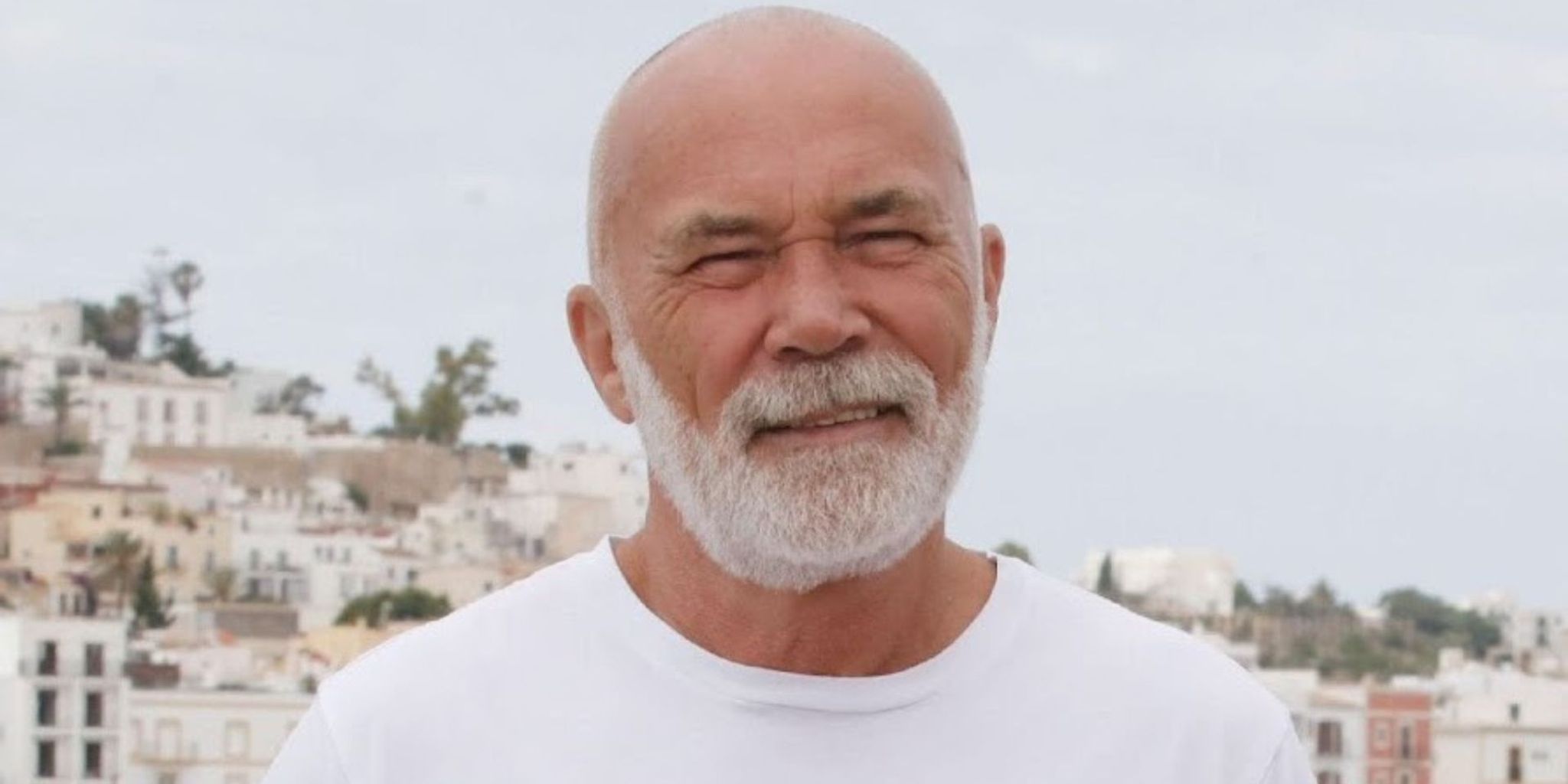

Born and raised in Stoke On Trent in the U.K., Danny Whittle had no designs on becoming a nightlife impresario. “I never ever thought I’d have a career in music,” he says, although he “loved music beyond belief.” He initially served in the military, sailing in aircraft carriers in the early ’80s. “My only comfort was reading books and listening to music,” he says.

Danny at Space Terrace 1998

Danny’s mother raised him on American soul records by the likes of Marvin Gaye, Al Green, Diana Ross, and Stevie Wonder. Everyone else in his mess deck only listened to rock and roll, though.

“I remember one guy coming up to me one time when I was listening to George Benson,” Danny recounts. “He said, ‘There’s another ‘f****t in the next mess.’ You know, it was that typical, macho military bullshit.”

“I went looking for him, because I thought, ‘I need to meet this guy,’” Danny says of the rumored fellow George Benson fan. The two did meet — on an aircraft carrier on Christmas Eve. The man’s name was Paul Whitehouse, and to this day, he and Danny remain best friends. “He’s the godfather of my son, and I’m the godfather of his son,” Danny says.

The two traveled the world on that aircraft carrier. Danny recalls, “While everyone else went off getting drunk and going to rock concerts, we went out and found the local discos.”

Danny Whittle with David Guetta 2007

On one occasion, Danny and Paul went into a Black club in Jacksonville, Florida, oblivious to the racial divide still lingering in the Southern United States. “We were looking like we were gonna get murdered,” Danny says. “But then we spoke English with an English accent. Suddenly, it was like we were Black. They loved it.”

“We were so naïve, we didn’t know that was not a done thing in 1981,” he continues. “But we were on the dance floor with them moving and grooving and having a great time through naïvety — but mostly through the love of music.”

After the military, Danny Whittle joined the fire brigade. Ten years of firefighting later, he developed corneal ulcers in his eyes. He went to the local job center, hoping to find a new career path. Instead, they signed him up for six months of financial assistance.

Six weeks later, Danny received one of his career-defining phone calls. It was Geoff Oaks, the founder and main promoter of the iconic Renaissance event brand. Danny declares Geoff “one of the best promoters of the late ’80s and early ’90s,” noting that Renaissance billed “people like Sasha & Digweed, Dave Seaman. He followed a sound — some incredible music.”

Danny Whittle, Pino Saglioco, and Paul Schindler

“Geoff said, ‘Why don’t you come work for us? Why don’t you do logistics on our tours, events, festivals, and so forth?’” Danny recalls. “So I said, ‘Okay, I’ll do it.’ What I quickly realized was that I had the ability to get out of bed in the morning and actually make things happen, to apply the professionalism of the military and Stoke Fire Brigade, in a young electronic music world of cowboys.”

“Not in a bad way,” Danny clarifies of the UK dance music landscape in the wake of the acid house explosion. “I mean industry people finding their feet, becoming successful quicker than they thought, and not realizing that when you tell a venue you’re going to be there at 7:00 in the morning to start production you can’t rock up at 10:00 saying, ‘Sorry, I lay in.’”

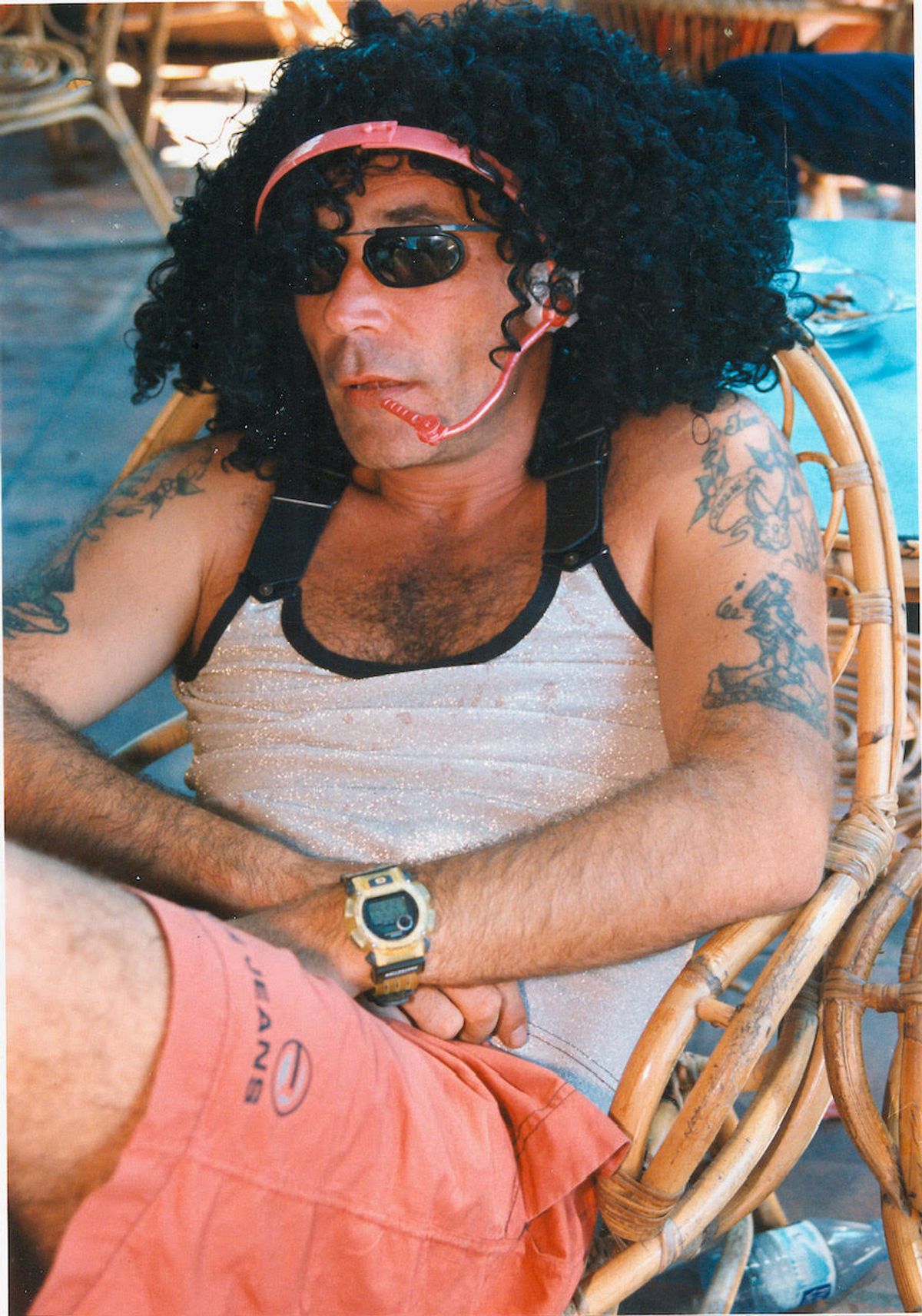

Danny had visited Ibiza on holiday years before, but working on Renaissance afforded him his entree into White Isle nightlife. The Ibiza incarnation of Manchester-born event brand Manumission drew 10,000 revelers every Monday in its heyday. One such occasion saw them partner with Renaissance and, in turn, Danny.

Ku Ibiza 1989

“I remember we had to hang a load of these fake clouds on from the roof of Ku, and you know how Ku is,” Danny says. “It’s like a football stadium. We had these ladders but nothing to lean them on, so I had four guys at the bottom of the ladder holding it up while I went and hung up these massive clouds. They were aluminum frames of chicken wire covered in this white, fluffy stuff, and then we dropped strobe lights in them. That night we created a thunderstorm in the club.”

“It looked amazing,” Danny grins, “but again, no health and safety. Zero professionalism — outside of getting there on time — but 10,000 people in the club that night having the times of their lives. That was 1996. It was my first introduction to Ibiza, which I absolutely loved. At that point, I knew, ‘I’ve got to live there. That’s my kind of place.’”

Renaissance would send Danny Whittle back to Ibiza for weekly Wednesday events at Pacha the following summer season. “I fell more and more in love with the island, with the whole concept of what Ibiza was,” he recounts. “I got into the history of the island, and I went back again to work. Then, I sort of got poached by Ministry of Sound, running their event at Pacha on Friday night.”

Ministry of Sound was, at the time, booking Chicago house figureheads like Frankie Knuckles and Derrick Carter as well as NYC and UK talent such as David Morales and Jazzy M, respectively. Danny aided in the London superclub-turned worldwide mega brand’s Ibiza operations until he was plucked away by yet another historic clubland player.

Fedde le Grand, Eddie Dean, Erick Morillo, Hugo Uriel, and Danny Whittle

“I went back to the UK, and then I got headhunted by a company called Home, who were building a big club in London’s Leicester Square at the time,” Danny says. “They asked me to work on their festivals. I didn’t particularly believe in the club in Leicester Square, but the festivals I loved — and I love Darren Hughs. Darren was the main man for Home, who used to be one of the owners of Cream, and he asked me to work on his outdoor events.”

Danny oversaw Home’s Winchester Bowl, which drew roughly 40,000 attendees, as well as gatherings in Dublin and Edinburgh. To his delight, the brand also sent him back to Ibiza to manage their newly launched event series at White Isle superclub Space.

“At the time, Space on Sunday was legendary. It used to open at 8:00 in the morning and close at 7:00 in the evening — but then everyone would go to Bora Bora or La Escollera,” Danny explains. “I said, ‘I think I can get Space from 7:00 in the evening on Sunday until 6:00 in the morning. Then we can do a 22-hour party all the way through. All we have to do is drop in Paul Oakenfold, Carl Cox, Sasha, Laurent Garnier, some big name, and I thought we could create the first 22-hour Ibiza party to run on a regular basis.”

Danny continues: “By week three, it was a roadblock. Oakenfold was a roadblock. Carl Cox was a roadblock. It just exploded, and anybody who was around at that time will tell you that’s what happened.”

What came next? “Then, Home went bankrupt,” says Danny.

The space occupied by Home was rebranded as We Love. Now a free agent, Danny Whittle celebrated the turn of the millennium helping throw a 20,000-strong party called Mobile Home at Bondi Beach in Sydney. During a layover on the way home, he received a call that marked the biggest turning point in his career.

“It was Ricardo Urgell from Pacha,” Danny says with a smile from ear to ear. “He’d obviously seen what happened at Space, and so he said, ‘Listen, why don’t you come to live in Ibiza and run Pacha.’”

Danny goes on: “It was like all my stars just aligned right there. That moment was everything I dreamed of since 1996. Four years later, one of my heroes, the owner of Pacha, calling me saying, ‘Come and live in Ibiza. Come program Pacha — the whole nightclub. I’ll give you a villa. You can live there. I’ll pay you good money. You can book what you want. You can do what you want. Will you come and do it?”

“I just went, ‘Yes,’” Danny says. “‘I’m going.’”

Danny Whittle argues that he helped Pacha usher in a new era of prosperity. He refined the statement made by Pacha as a brand, which partly meant putting the DJs front and center. “They didn’t understand that content was king,” he points out. “At that point, you could put Carl Cox in a skip down the road and it would be packed. You could put somebody else in the best nightclub on the planet and it would be empty.”

This meant cutting third-party organizers out of the equation. “They had this goose that lays golden eggs, but they didn’t really realize it,” Danny explains. “They were letting too many promoters come in and steal the thunder of their brand and their venue. I cut that out. I changed it to where we booked DJs direct.”

Under Danny Whittle’s leadership, artists like Pete Tong, Erick Morillo, and Luciano held residencies. Ditto for superstars like David Guetta and Swedish House Mafia, whose radio and festival-ready interpretation of dance music would soundtrack the EDM movement of the following decade. Amnesia and Space soon followed suit. They wouldn’t be the last by any means.

Danny Whittle x Eric Morillo 2002

“Within three years, they all started to do it. They started to realize that they didn’t need the promoters anymore. The DJs, agents, and managers started to understand that if you’re not paying a middleman promoter, you can pay the DJ more, which means the agent gets paid more, which means the manager gets paid more, and so on. So, DJs and agents and managers quickly swung onto the idea,” Danny says.

The ripples of Danny’s influence reached far beyond the White Isle. “About 2003, 2004, all the guys from Vegas and New York all came over to Pacha — and the whole landscape of Vegas changed,” he argues. “They watched what was going on in Ibiza. Instead of doing big shows with names like Celine Dion, when I went out there a year later, all the bills had Tiësto and Swedish House Mafia.”

Las Vegas made a grand entrance into the conversation on dance music leading up to and during the EDM boom. According to the Bar & Restaurant Expo, in 2014 nine of the highest-grossing nightclubs on earth were based in Sin City. “It wasn’t club brands. It was presenting the artist like the artist mattered to, say, Live Nation,” Danny says.

Clubland eras are famously ephemeral, and Danny Whittle’s tenure with Pacha came to an end in 2013. For that, he blames “a little argument with my hero, which was the stupidest argument ever.”

The jury isn’t out on whether exorbitant DJ fees have equated to a net positive or negative for club culture. In 2013, Ricardo Urgell, the Pacha founder, decided it was the latter. “At the end of the day, it was just hard for Ricardo — somebody who had run nights since 1964-1966 since the death of [Spanish Dictator Francisco] Franco — to understand why a DJ would get paid €50,000 for two or three hours of work,” Danny says. “It wasn’t hard for me to understand, because the night was making half a million.”

Danny continues: “As much as he liked the bank accounts and all the rest of it, he came into my office one day and went, ‘Right, I need you to halve all the DJs’ salaries for next summer.’”

Danny Whittle and the IMS Partners

“I said, ‘Ricardo, I can’t do that. If I do that, they’ll all leave. There are five other nightclubs on Ibiza that will pay them that money. Managers will tell them to leave. Agents will tell them to leave. Please, I cannot do that. We already get a really good deal. They want to play Pacha. We’re an iconic brand, an iconic nightclub. We make a huge amount of money. Don’t ask me to do that,” Danny recounts.

“He said, ‘Well, if you don’t agree, maybe it’s time that you left,’” remembers Danny. “And that’s exactly what happened. I went, ‘Okay, I’ll fucking leave.’”

According to Danny, Ricardo had to pay him a substantial severance, and the club lost money hand over fist. “Remember,” he says, “Luciano left with me, Defected left with me, Pete Tong left with me, Erick Morillo left with me. So, four of the biggest nights all went, and they had to pay more for the ones they kept.”

Danny says that he and Ricardo have since resolved their differences. “Now we see each other, and he hugs me like a long-lost son,” he says. “He knows that it was stupid what we did.”

While still at Pacha, Danny Whittle helped launch an electronic music conference that would go on to serve as an annual mile marker of the industry: the International Music Summit (IMS) in Ibiza.

This time the catalyst was not a phone call, but a “drunken idea,” according to Danny. “Me, Pete Tong, Ben Turner, and Martin Netto were up on the roof of Pacha like we were pretty much every Friday when Pete was DJing. Well, we were up there every night for about 130 nights in a row. But every Friday, the roof of Pacha was like an English pub, basically, and everybody from the industry was up there.”

Danny Whittle with his son at IMS 2023

Danny says that the four of them got to talking about how Winter Music Conference (WMC) had, in their opinion, dropped off as an industry gathering. Miami Music Week, which coincided with WMC, began to draw more spring breakers than industry professionals.

“It was an amazing time, but we saw it was tailing off as a conference. We were like, ‘Oh, let’s do an Ibiza music conference, let’s do an Ibiza music summit. And we were like, ‘Ohh yeah, let’s do it, let’s do it,’ and instantly forgot the idea the next day,” Danny laughs.

They eventually pieced the idea together again and discussed it off and on for a couple of years. Then, in 2007, Danny Whittle, Pete Tong, Ben Turner, Mark Netto, and Simeon Friend each finally put in $30,000 towards the following year’s inaugural event.

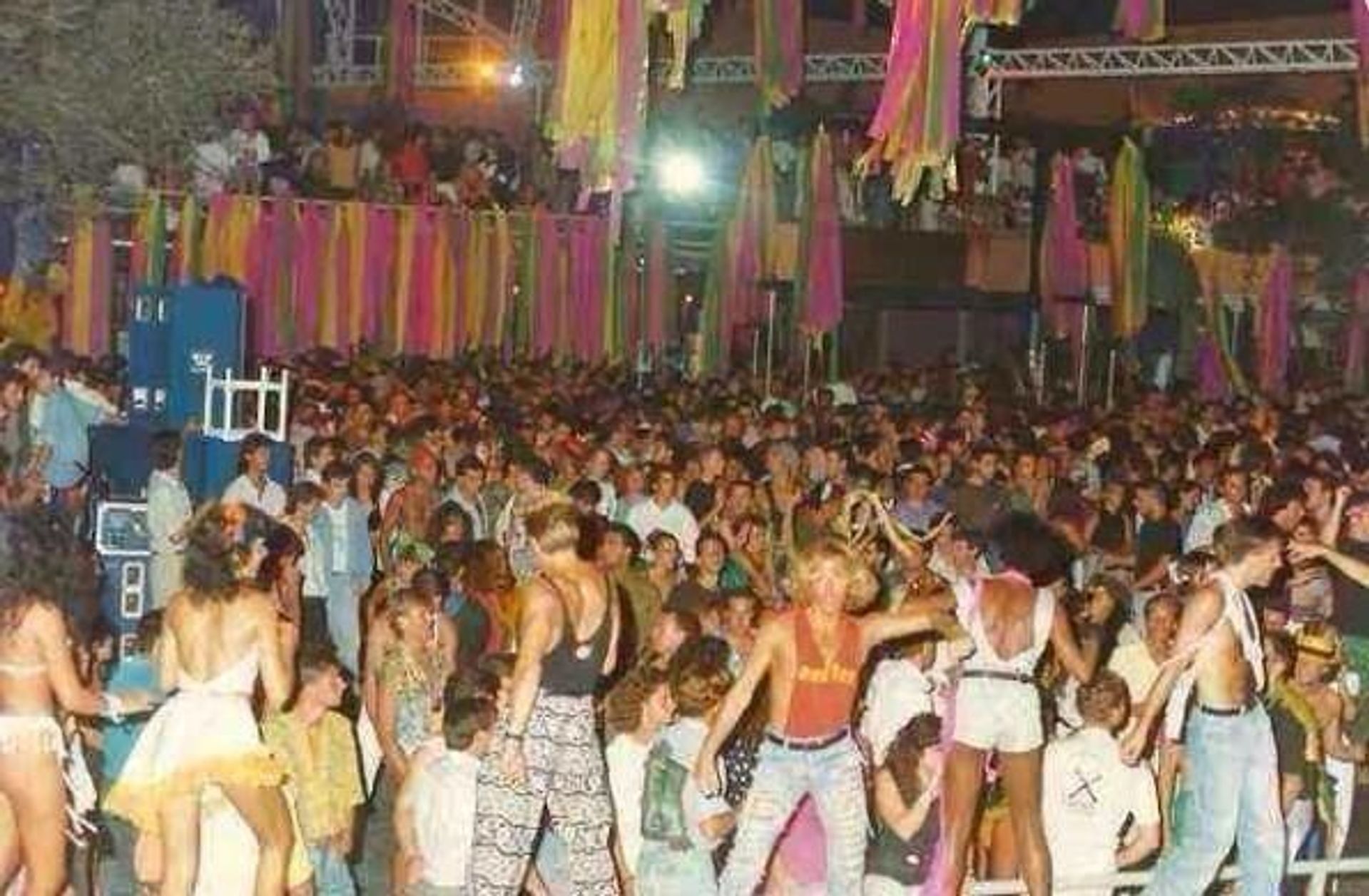

For the first IMS, they partnered with Hotel Fenicia in Santa Eulària and held their grand finale at the tennis court of Pikes Ibiza. “The first one lost a fortune. About 90 people showed up,” says Danny. “But there was a really cool vibe about it and everybody was so happy they were at the first one. The finances weren’t ideal, but it just felt really good.”

The sophomore edition marked a turning point. IMS 2009 moved to the Ibiza Gran Hotel, and the town hall allowed Danny and company to hold the finale in Dalt Villa, a 5th-century district built atop fortified walls now protected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. “Then, everything changed,” he says.

“We’re still the only people allowed to do anything there outside of the medieval fair and a sit-down jazz thing they do. We’re the only ones who can do a rave,” Danny explains. “When you stand up there onstage and you look at 3,000 people raving like that, you think, ‘What were the Romans doing here 2,000 years ago? Or the Phoenicians, or Arabs, or whoever?’”

IMS, which Beatport acquired in 2023, has not only succeeded but continued to expand. The event often sells out all the rooms at participating hotels, but attendance isn’t the only metric that matters to Danny and his partners. He says that IMS hasn’t been connected to “a single arrest” throughout its history so far, “or a medical issue or anything.”

Now, Danny has a new project: Club Chinois. 1930s Shanghai jazz clubs inspired the space’s decadent decor, not the least of which is a disco ball hanging down from a giant, circular chandelier over the dance floor. Delays caused the club to open in July of 2022, forcing them to scramble for bookings. The owners nonetheless managed to lock in a Saturday residency with Luciano, who put them in touch with Danny.

“I got introduced to Sid and Sofijah, who are the owners. Amazing people. There’s a great team, they just opened late,” Danny says. “I spent The first sort of month fire fighting, just trying to fix the problems that they had already because of bad timing … And I think once I got involved they could see me sort of steady the rocking ship, make sure that things got dealt with. A bit at a time, the ship stopped rocking.”

Club Chinois Ibiza

Danny continues: “Once you start finding stability and people start talking about you in the right way — and not the wrong way — then you start to gain momentum. By the time we got to October, the club was just getting busier and busier, and by Halloween, we literally turned 2,000 people away.”

Club Chinois is smaller than the world-famous superclubs on Danny’s extensive résumé, to be sure. “In reality, it’s a 1,300-capacity club,” he points out. “It’s not a huge nightclub, which is partly why I took the job. I didn’t want the job of a 4-5,000 capacity club anymore. It’s just too much pressure.”

That’s fair, considering Danny Whittle’s accomplishments in dance music leave him with nothing left to prove. What adventures may come are bound to find him, though. As the tides of the industry turn, it’s only a matter of time before duty calls, and he finds himself drawn to the next dance floor.