Neo-American Techno: Richie Hawtin and the New Wave of American Minimalism

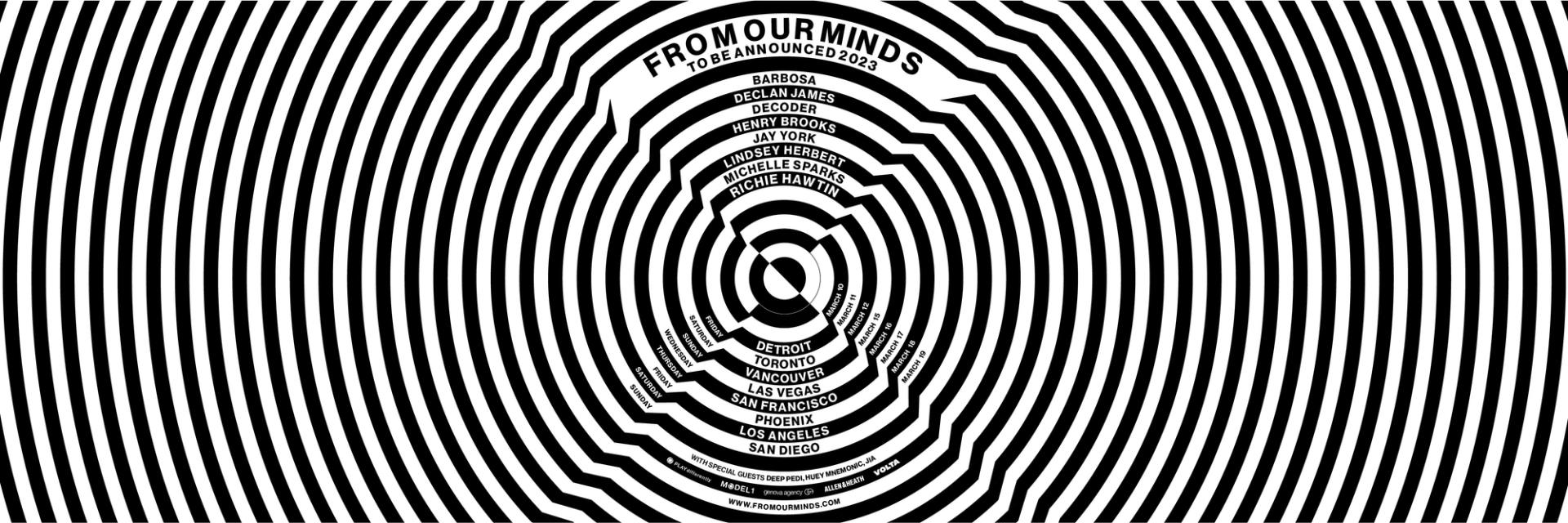

A drizzle of Southern California rain falls in the downtown San Diego twilight as techno patriarch Richie Hawtin finishes his set and steps offstage. As his first North American tour in nearly half a decade concludes, he crosses the concrete plaza of the Quartyard Brewery and ducks into a large, matte white corrugated steel shipping container outfitted as a green room. “It’s the end of our eight-date From Our Minds tour across North America — warehouses, underground,” Hawtin tells Gray Area.

The tour started in the birthplace of techno, Detroit, moved through the western US and concluded in San Diego. Every tour stop featured the techno forefather alongside a hand-selected bevy of emerging North American artists, each with particular tastes and styles.

“I don’t know what [the new wave of American techno] is,” Hawtin says with a subtle frankness. “But, I can say I’ve been around for 30 plus years,” he says in a turn of authoritative confidence. “America, for real, focused techno, is probably at its best that I’ve seen in 25 years. Maybe it’s the best ever.”

The artists enlisted to travel and perform on this North American tour are an eclectic mix across a wide geography who share a singular passion for pushing experimental, uptempo techno sounds. They collectively view electronic music through the generational prism of a completely interconnected, post-COVID digitalized world.

“We’re all working together, we’re friends with the people who came before us. And they’re our peers — we all have this mutual respect for each other,” says Phoenix-based Lindsey Herbert, the artist and co-founder of EvilGroove Records. “[It’s] nice to get that kind of recognition and affirmation of those who paved the way for you.”

Toronto-based Barbosa, founder of the label and party series Heist Mode, is circumspect as he considers the ongoing relationships between his fellow artists and Hawtin.

Barbosa

Factory 93

“In order to produce what we’re doing, you truly need to be DIY. You have to be a producer because the music, after all, is what we’re trying to display,” he says about creating a unique sonic experience. “We really connect because we are producers, we are label owners, we are event producers. Keeping it very authentic and keeping it genuine is what brings more people into that fold.”

So a big important piece is having someone like Rich, who is the front runner and who helped start and get this movement going back in the late 80s [and] early 90s,”

For Hawtin, organizing and promoting such tours is a welcome reminder that musical ideologies transcend mainstream culture across generations.

“Techno’s bigger than its ever been, and there’s a lot of big parties and a lot of big DJs and Instagram and all that,” he says. “It’s very comforting to realize that there’s a lot of people making music in North America, listening, dancing to this music. Searching out something a little bit more alternative.”

FAST MINIMAL

“This tour is about rhythm and bass. Giving people just enough to move their bodies and not fill them with too many melodies or too many samples,” Hawtin explains. “Just giving people room within the music to dance and move — I don’t think that’s happening so much.”

“Techno has become quite formulaic,” he asserts. “I think what we’re trying to play is something different.”

“I always had this idea of minimal [techno] as how Richie, Dubfire, and [Hawtin’s label] Minus sound. But it’s cool because there’s this new wave,” Lindsey Herbert says. “We’re calling it ‘fast minimal’. It’s always got that groove and some kind of element of trippyness, something that makes you feel an emotion.”

The underlying values and aesthetics of this new wave of American techno artists mirror the 90s significantly, Dallas-based label and event series VOIDWARE Declan James observes.

“I think each one of us has played a Planetary Assault Systems track on this tour,” James says of the seminal UK techno producer Luke Slater’s early 90s pseudonym.

When considering the global nature of popular techno music, Barbosa tells Gray Area, “in Europe, what’s big right now is more hard techno or hard trance. Music that is similar to the structure of EDM — big breakdowns, big drops, very melodic focus, vocals.”

These techno artists’ response is to return to minimal techno’s roots, particularly in a way that eschews popular internal structures.

“I truly believe that hard techno was consumed quicker during COVID with the crowd in America,” Barbosa says. “What’s happening is now that they’re consuming it, they’re looking for something more complex, or that gives you more to your body on the dance floor. That usually happens with very dynamic, very hypnotic music. It’s the core of dance music — having a groove, having a rhythm. Something that locks you in and keeps you going.”

BIG SPECTRUM OF TECHNO

“Declan James and Decoder — they are actually the sound of underground [American] techno,” says Jia. It’s a bold claim, but Jia knows what he’s talking about — after all, he’s the LA underground scene insider and founder of 6AM Group, who co-produced the LA edition of From Our Minds.

James and Decoder’s collaborative project Frame is relatively new — the San Diego tour stop is the sixth time they’ve performed together. Frame released “1076030” on Insomniac Records sub-label, Factory 93, last August.

After the tour concludes, James tells Gray Area about the general contours of those new fast minimal artists and the sounds he experienced on tour. “Everyone had their own style, but the theme was minimalists, 909 [and] 808 driven stuff that’s much more true to form techno than Drumcode style stuff. People were responding to the general sound of faster 909 [and] 808 driven stuff,” James notes.

James’s words hold weight, considering his history playing EDC in 2019 and 2021 on the Drumcode and the Factory 93-hosted stages, respectively. He also has releases on both labels and others, including Above and Beyond’s Anjunabeats and LA-based Space Yacht. James and his fellow artists’ sounds somewhat respond to the cultural commodification of previous waves of techno, all mainstream and underground varieties included.

Lindsey Herbert

“We all have our own different styles,” says Herbert. “My style is different from Decoder’s, who is very spacey, and Jay [York] is very groovy. Barbosa is a bit heavier. Henry is a bit more industrial and heavy. We scale a big spectrum of techno, but it still makes sense.”

James agrees with Herbert.

“There’s an overarching continuity between everybody in that we all work really well together as a group. In time, this will develop into something similar to different musical movements like New Wave,” James says.

“That’s what we’re onto here — the beginning of some sort of wave or movement of techno that’s going to be remembered as such in time,” James reasons. “It sources a lot from the timeless qualities of 90s techno without being too nostalgic. It’s traditional in form but still polished and novel.”

A half-hour before Hawtin’s tour ending set concludes in the downtown San Diego twilight, he is running tracks at 138 BPM — brisk but not overly frenetic. The pace moves similarly to Charlotte de Witte’s during her Ultra Music Festival mainstage set the following Friday in Miami. That set had Billboard asking if de Witte’s performance was “the first time a ‘serious’ techno DJ played the Ultra main stage?”

But unlike de Witte’s more digestible mainstage offerings, the sounds Hawtin plays are emblematic of techno: rapidly forming, oft-experimental juxtapositions such as those that Herbert endorses in her fast, minimal sonic aesthetic, James pushes in his blisteringly textural Lovecraftian minimal style, and Barbosa purveys a heavily layered darker minimal material.

It’s about speed and complexity.

“Music is something to get lost in. Hypnotic frequencies that allow you to step away from reality and lose yourself, and then find yourself,” Hawtin says. “That’s what it’s all about.”

Declan James

COOL TO BE WEIRD

“Now it’s cool to be weird,” says Barbosa. “Crowds in North America, they’re not conforming. So it’s cool to like EDM and techno, and it’s cool to not wear black or wear all black. You see some old heads, but you also see very young people, new people. People are dressed very differently — you see every type of person.”

The focus on personal aesthetic authenticity “was something that was common with ravers in the 90s and early 2000s,” he says. “Now this new generation, kids from 18 to 22, they have the same mindset. It’s cool to be authentic — even if it’s not something that many others like.”

“People are there from the beginning till the end, they’re not there for a headliner [because] we keep it A to Z, we don’t post set times so the energy is there right from the beginning to the end,” he says. “It’s a new type of energy yet it’s also kind of nostalgic of rave crowds back in the day.”

Herbert agrees with Barbosa.

“Each stop was so special in its own way,” Herbert says. “It was also really cool to get to see Richie in some of these smaller, more intimate or underground spaces where he felt more freedom to play how he doesn’t sometimes. It was great for everyone, merging the generations at the events:”

“Tours like this have a lot to offer that type of connection,” says Michelle Sparks, a Phoenix-based producer, promoter, and co-founder of Circuit. “It’s cool to see local promotion companies outside of the Live Nation owned massive corporate promotion companies — it’s nice to connect the dots on that and see the promoters on the [tour] stops. That will ultimately create a network amongst the smaller promoters as well as the artists on the tour. That’ll do a good amount in every city to build that underground community and that safety net for techno out here [in America].”

As for an overarching perspective on the state of American techno, Hawtin tells Gray Area that “there were always pockets. But the pockets of techno in North America are now connected, and they’re really reflecting on what this music is all about.”

DANCE IN DARK PLACES

After the tour’s final show concludes, Hawtin and the gathered artists retreat to a Japanese restaurant on the corner directly across the street from the Quartyard. He holds court from the middle seat of a long black lacquered dinner table while the group gobbles sushi. Then, in true Hawtin style, he pours chilled sake, and glasses clink together in a celebratory end-of-tour toast.

What has he learned from supporting and integrating with this next wave of American techno producers and listeners?

“What this tour showed me was that there’s still a lot of weirdos out there who want to meet other weirdos and dance in dark places,” Hawtin says with a quiet, wry chuckle.

Basking in the afterglow of a wildly successful eight-stop North American tour, Herbert knows his new wave won’t last forever. “Now there’s people even coming after us, newer DJs from after COVID. Kind of brewing. It’s exciting,” she says. “I love to see more people doing it, and I love to see techno growing [in North America].”

Barbosa hopes tours like this inspire others in similar pursuits. “I hope that we’ve inspired others to do what we’re doing. Just do what you believe in. And if this type of an experience was something you like and want more of, then the best thing you can do is to connect with others who do it,” says Barbosa. “And if there’s no one else, just do it yourself.”

Herbert feels similarly when asked about her thoughts on this next wave of techno artists and their ongoing impact on electronic music.

“Trends come and go,” she says. “What will always remain is the true, pure, no BS kind of stuff that us [artists] on the tour are all about.”