The World Has Once Again Fallen in Love with Raving

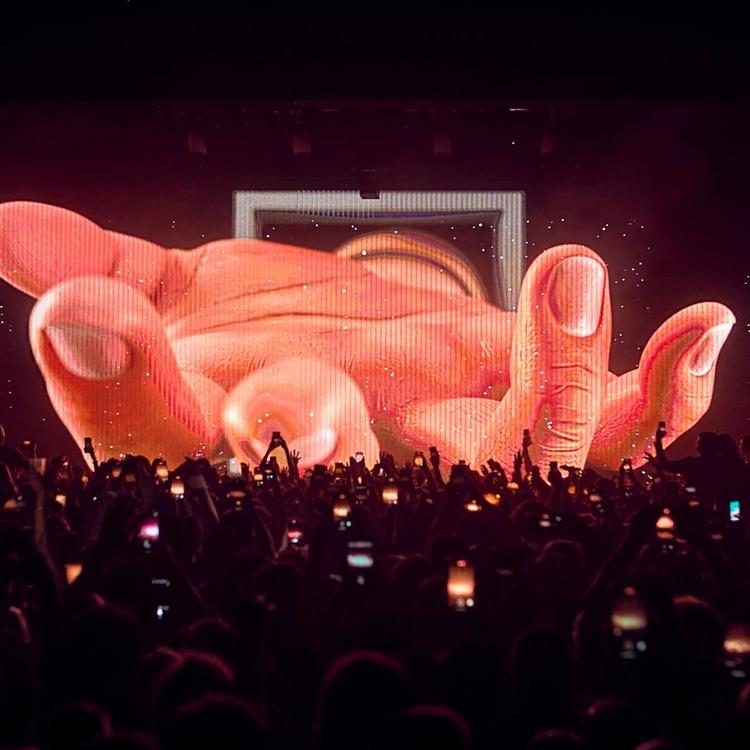

The world has once again fallen in love with raving.

Given the general conglomeration of what a “rave” is, it might seem like the world has always loved raving as dance-forward festivals and club culture explode around the globe.

Beyond the typical forums, every sushi restaurant and grocery store plays house music these days (not to mention the co-opting of the genre by major pop stars like Beyonce and Drake), so how could raving get any bigger?

Well, it comes down to the music. In the same way cultural gatekeepers are feral in attacking any comparison between house music and EDM, certain forms of dance music, comparatively, have more or less of a “rave” quality to them, and that distinction stems from the energy they bring to the dance floor.

When raving first exploded in the 1990s, it was a new phenomenon built around marginalized people like those in Black and gay communities coming to a safe space where they could freely express themselves and release the energy of oppression.

In the last couple of years, especially since pandemic-era restrictions faded, the music has reflected that era as the world brings those years of pent-up energy to the dancefloor.

Those who discovered dance music via Twitch streams are finally engaging in their first dance music experience and putting some wear and tear on their dancing shoes. Old(er) ravers have been ecstatic to return where they truly belong. This energy and desire have led to a coinciding effect in the music that’s resonating with the community. An effect that’s made the music far more ravey based on certain qualities.

One strong indicator of “ravey-ness,” as it were, is tempo.

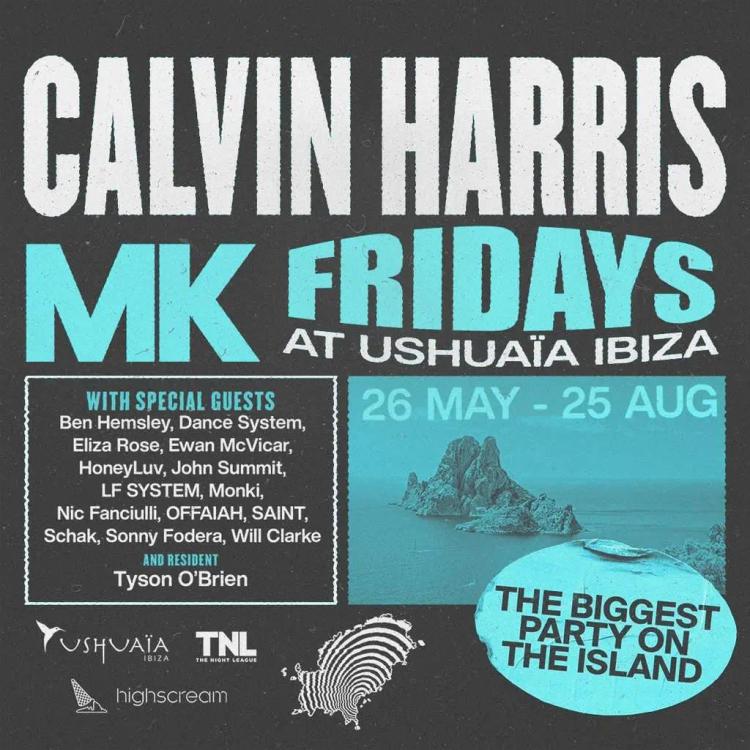

High-tempo genres like UK garage dominate the zeitgeist as seen in hits like “B.O.T.A. (Baddest Of Them All)” from Interplanetary Criminal and Eliza Rose, which is sitting at over 199 million on-demand streams on Spotify at the time of writing.

Another indicator is the type of synths that are driving the tracks. Rave music synths are like the flashy and coruscating bleeps of the 1999 classic “We Like To Party” by the Venga Boys.

“We Like To Party” is undoubtedly one of the most famous rave tracks of all time, and one that harbors a similar quality to the breakout single from Schak, “Moving All Around (Jumpin’),” featuring Kim English, released on the UK stalwart Patrick Topping’s record label, Trick.

Since its inception, Trick has pushed these ravier sounds. High tempos. Hype synths. Music that celebrates the ravenous release found on the dancefloor.

Another hit from the label is Ewan McVicar's soulful yet ecstatic interpolation, “Tell Me Something Good.”

Following the reignited trend of sampling vocals from a past era, McVicar literally just took Rufus and Chaka Khan’s vocals from the 1974 classic of the same name, threw it over a four-on-the-floor kick, a storming bassline, and made it ravey as hell.

It’s almost as if the larger-than-life synths (laid out in a call-and-response-fashion) are the “something good” that Khan wanted to be told.

More than these tracks being hitters at the club, the high streaming numbers (“Tell Me Something Good” has over 60 million on Spotify) indicate that people listen to them casually. In the car. On their headphones.

People are sending these tracks to their friends to spread the word of the rave, and not too long ago, ravers were afraid to spread that word. There were quite a few years in dance music history when the word “rave” was straight-up taboo.

There’s always been some stigma around raving—hence the introduction of the RAVE Act in January of 2003 by Joe Biden—but the tragic death of a 15-year-old attendee from a drug overdose at EDC 2010 in Los Angeles made the word “rave” even more divisive.

Telling someone you were into raving took a certain amount of trust, as those outside the culture often sneered upon hearing the term. No matter how you presented yourself day-to-day, all skeptics could see was someone out of their mind on substances in a fluorescent, scanty outfit.

Often, people would keep their raving inclinations secret to avoid the ire of judgemental people whose only reference was what they heard on the news. Good thing ravers had the dancefloor. Caging one’s true self uses up a lot of energy. A place to release it is required.

The industry was distancing itself from the term as well as event promoters were facing their version of the stigma through uninspiring ticket sales and restrictions from the authorities. For example, following EDC 2010, large-scale electronic events, like those of major promoters such as HARD and Insomniac, were banned from Los Angeles.

In the trailer for HARD Summer 2015, the event’s founder, Gary Richards (a.k.a. Destructo), says:

“HARD Summer’s not a rave. It’s a music festival.”

Whether that particular event was or wasn’t a rave is debatable (although having headliners like Jack Ü, Zeds Dead, Dillon Francis, and Porter Robinson is pretty darn ravey), but the fact that a prominent member of the rave scene like Richards would make that distinction is demonstrative of how the public perceived the term.

Yet another, and the most prominent, way the stigma towards the word “rave” manifested was through the music.

EDM, the music that opened the floodgates to clubs and festivals in the United States, is rave music. What it lacked in tempo, it made up for in having the biggest synth sounds known to man (hence the subgenre most associated with EDM is called “Big Room”).

The current wave of rave music, came in response to a massive release of energy. America finally understood the power of dance music, and they were throwing themselves at it with full force.

But eventually, the stigma against the “rave” caused the fall of EDM.

EDM is one of the most stigmatized terms in music, and perhaps popular culture. Something about that sound and the massive parties that came with it has never sat right with those who prefer gentler genres.

Anthony Gonzalez of M83 just reignited the stigma in a recent interview with Consequence stating:

“EDM is probably one of the styles of music that I hate the most. All of a sudden, I have these bro EDM DJs playing my music, and I just can’t even care less. Sometimes I wish that I could erase that fan base but I don’t think it’s possible to do that.”

While EDM was at its peak around 2012-13, most ravers shrugged off the stigma (as they should because that music is still so much fun), but eventually, the sneering took its toll.

People started looking for music that belonged in their newly christened environments of clubs and festivals but wouldn’t carry with it any judgment from the outside.

This intention brought about the rise of pop-friendly and more reserved dance acts like Disclosure and Gorgon City. Likewise, the oh-so-chill subgenre of tropical house and its purveyors like Kygo emerged from this era.

All those artists and their cohorts are certainly talented artists who earned their place in the ranks of dance music (especially Disclosure since Settle is a masterpiece), but their music is not at all ravey.

Big songs from this era, like Disclosure’s “Latch” and Gorgon City’s “Ready For Your Love,” are light, groovy, and chill. They carry a different energy altogether.

This era of music was not about a release. This music was about widespread appeal. Welcoming those alienated by the ravey-ness of EDM into the dance music fold, and these segue artists reaped the benefits.

Sam Smith was nobody before Disclosure featured him on “Latch,” and now he’s one of the biggest pop artists in the world. Such success can only come from universal appeal. Hence why Sirah, the vocalist featured on some of Skirllex’s biggest tracks in the EDM era, never made it big on her own.

The same artists emphasized their disconnection from the rave via their live sets. Raving relies on DJing. The constant flow of music that comes as a response to the crowd’s energy is essential to the experience.

In the first wave of their success, Disclosure, Gorgon City, and Kygo all opted away from DJing and implemented a live set.

Gorgon City brought a whole band on the road, featuring a drummer and vocalists. Disclosure and Kygo had hardware setups that featured beat pads and live instruments like bass and piano.

This was the furthest dance music ever went from the rave.

What brought about the change once again comes down to energy. Many who dipped their toes in the dance music waters with Disclosure were welcomed into the community with open arms by the ravers (because the ravers were also down for Disclosure, too).

Suddenly these new people realized the dancefloor was a place to release their energy. They saw that maybe those ravers were on to something before.

Then came key artists like tech house mavens FISHER and John Summit, who ushered in this transition.

Just like Disclosure was the segue from pop to the dancefloor, FISHER and John Summit were, to the dismay of the underground, segues from the dancefloor to the rave. Their music isn’t super fast or overly hype, but it has a more party-driven sound than Disclosure and the like.

Now intoxicated by the release of energy, everyone stopped caring about pop features from artists like Sam Smith. This is demonstrated by Calvin Harris’s new album, Funk Wav Bounces Vol. 2, in which none of the tracks have more Spotify streams than “B.O.T.A.” despite featuring superstars like Dua Lipa, Justin Timberlake, and Pharrell.

No, what people care about when it comes to dance music in 2023 is the former word of the title: dancing.

Showing up in a place where the music is loud as hell, they can dance however they see fit. It is a place where they can release all their energy pent up from a default world that’s increasingly anixiety inducing and stricken with turmoil, where the music reflects that release.

The name of that place is called the rave, and after raves were taken away from the world for almost two whole years, in some places even longer, any sort of stigma is irrelevant.