Pay Attention, Nala’s Bringing Rock Back into Dance Music.

As evening sunset drenches the LA Coliseum in a bath of warm magic hour light, Dirtybird Records artist and Mi Domina founder Nala strides amiably under the Olympic cauldron and across the concrete stadium pavilion. As she nears the guardrails overlooking the cavernous inner stadium, she pauses at a wooden picnic table to sit for an interview with Gray Area. From there, she soaks in the colorfully psychedelic sights, sounds, and splendor of Desert Hearts Los Angeles while talking shop.

As a central producer and artistic driver in the ever-evolving North American tech house scene, Nala’s resume overflows with accolades and accomplishments. She’s an oft-featured Dirtybird player, collaborated with label head Claude VonStroke, and enjoys a close advisory relationship with both Barclay and Aundy Crenshaw after being officially managed by the dynamic Dirtybird founding duo throughout her initial professional years. She also works closely with major artists like Walker & Royce, the trio dropped “Not About You” on Chris Lake’s Black Book Records last September to widespread acclaim.

“My entire goal is to emphasize that my contribution to dance music is coming from a rock perspective, an indie-dance punk perspective,” she tells Gray Area. That focus on marrying punk and indie-rock with dance music is a genuine, deliberate choice to pursue her unique tastes. “I get annoyed when something is too common — I rebel instantly,” she says.

Even the recent wardrobe choices for her DJ performances mirror that rebellious predilection. “I was wearing a lot of black. A lot of my friends are wearing black. The techno community wears all black,” she notes. “And I was like, I can't do this anymore. Imma wear all white [when performing] so I could separate myself, my own identity. I just feel better that way. But now I call it my work uniform. It's getting ready for the job, twisting knobs and stuff. [My] suit of armor.”

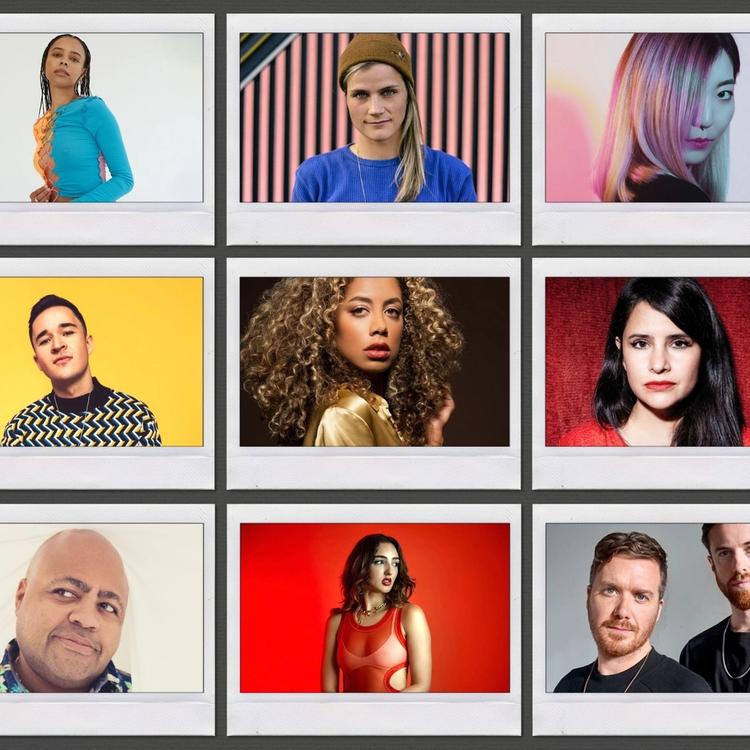

Nala at EDC 2023

Nala’s ongoing dedication to sculpting a unique artistic identity is undeniable. Coupled with ever-sharper production skills and an uncanny ability to cleverly tap into the cultural zeitgeist with her lyrics, it’s not surprising that DJ Mag North America nominated her for breakthrough producer of the year.

“Part of me is an Aries, so I'm a little competitive,” she ponders as she considers her nomination for the coveted award. “But I'm just grateful to be considered for my work. I've fought a really long time to be acknowledged in this way.”

NEW IDENTITY

“I still work with [Barclay and Aundy Crenshaw], [but] I am trying to branch out,” Nala says of her working relationship with Dirtybird. “It took me a couple of months to figure out where my footing was as an artist outside of Dirtybird, even though I'm still touring and releasing with Dirtybird.

“I was talking about this with Walker & Royce — [Barclay] has the best taste. He knows how to hear things and make them the best they can possibly be. It was through his vision that I was able to really level up. Now, I'm like, 'how do I take that and go even further?'”

Nala’s upcoming releases may hold the answer to that question. She's again turning her gaze inward and critiquing broader cultural and social norms. “A lot of the music I’m releasing this year is growth-oriented. I have a song that’s on Club Sweat in Australia [called 'Growth']. The whole lyrical theme is growth and being a better person — acknowledging that you have wrongs and being an adult about it.

“On the opposite side, I have a song called ‘Me Me Me’ with Catz ‘n Dogz. That song is just about sex, wanting and desiring someone. I try not to dabble too deeply into that — I don’t want to only ever write about sex. But once in awhile is fine,” she says with a laugh.

“Then I have a song called ‘I Don’t Mind’, which is more interpersonal relationship stuff. This year I’m doing a lot more relational writing based on the most pressing issues in my life," she explains. “Friendships that I’ve outgrown. [Experiences] that you just have to write about when you’re going through it.”

CONFESSIONAL ARTISTS

Nala's energetic, adroitly cutting social commentary vocals are a hallmark of her music. And she's more recently begun to incorporate them live into her DJ sets.

“[Vocally], I do a lot more punk, spoken-word, indie stuff. I consider my vocals and the way that I sing like an indie boy band — like I’m the boy band lead singer," she says with a bright laugh. "I’m not Ariana Grande — I’m not doing some crazy vocal runs. I’m like some cute little indie boy.”

“With my label [Mi Domina] I'm trying to curate a very specific niche, which is really palatable, fun acid house or punk,” she says. “Punk rock is real. It’s relevant to how we experience our lives. Unless you're living in a bubble of perfection — then congratulations!” she says with an incredulous chuckle.

In this way, Nala is reframing late 90s/early 2000s pop-punk and indie-rock conventions through her current perspectives. Forward-thinking artists have utilized a similar tact across various emerging subgenres in recent years — most apparently by pioneering hyperpop artists such as 100 gecs, Dorian Elektra, and glaive. The central difference between such artists and the rest is that many songs get created in a cultural vacuum, resulting in inauthentic, caricaturesque lyrics. It’s not that Nala thinks generic dance music featuring empty-calorie lyrics shouldn’t exist. That’s just not the type of experience she hopes to provide with her music.

“I’m not here to be escapist [with lyrics],” she says bluntly. “The instrumental itself is the force of escapism.” Accordingly, she pursues a definitively different approach to writing electronic music — one that’s decidedly personal and smartly subversive.

“Confessional artists,” Nala tells Gray Area. “It's something I learned based on how Gwen Stefani writes. It’s also part of my philosophy — part of our job as artists is to dissect the human experience and make it palatable for everyone else. So the driving force behind my lyricism is: ‘How can I say what everyone is avoiding and make it so it's not offensive, [but] we can still dance to it?’ However you digest them, it could apply to your life [in] a number of ways.”

As for the bottom line of her ongoing work in electronic music? “My main thing is trying to touch on the human experience,” she says. “Why else would I make art?”

As for the “main message for the next few years” that she seeks to convey to her rapidly growing legion of dancers and punks?

“Just pay attention to the fact that I’m bringing rock into dance music again.”