The Past, Present, and Future of Ghettotech with Dj Godfather

There are already a vast amount of online articles and Wiki stubs that will give you a history lesson in ghettotech. The Red Bull Music Academy has a great in-depth oral history of the genre, outlining how Jeff Mills’ unique scratching method set the genre in motion. You can even carve out some time to read a heavily sourced 100-page master thesis that goes deep into the ethnomusicological side of ghettotech’s history in Detroit and beyond. Hell, our sister site Festival Insider even has a brief overview of ghettotech’s origins in its Road Trip series.

So no, this is not another Wikipedia stub - the outline of ghettotech’s history is already very well documented. Instead, we’re taking a trip down memory lane with one of the longest reigning ghettotech pioneers, Brian Jeffries, better known as DJ Godfather.

From the start, ghettotech has been “straight up, Detroit shit.” As a Detroit native and current resident, Jeffries has not only had a front-row seat to the beginning of the genre, but he’s also one of a handful of pioneers today still actively touring and releasing music. In fact, he may be at the strongest point of his career.

“Honestly, 95% of my sets now are all my records.” Jeffries relays. “Cause during Covid, I did 189 songs mixed and mastered in 10 months.” Like others confined to their homes, Jeffries refused to sit idle, “I took advantage of the time and instead of getting frustrated and pissed off, I was like, ‘you know what, I’m gonna do these projects I wanted to do.’”

And that’s exactly what he did. Releasing a 44-track album last year called Electro Beats for Freaks, Jeffries intentionally blended the new tracks, so the album played like a DJ mix. At a time when many artists in the fore and underground are only releasing singles or EPs, a two-hour continuous mix of new material seemed a risk. And many of his peers raised their eyebrows at the concept, “Because they’re too lazy to do big projects.” he says confidently. “I’m like, ‘you know what guys? You do your singles but I’m gonna do something that’ll stand out.’”

When he started DJing and producing, Jeffries only had one goal in mind, “I just started doing shit for Detroit.” he shares his modus operandi. “Back then, there [were only] like six or seven record stores that are poppin’ and if you had a good ghettotech record in Detroit, you could sell 2000-3000 copies, just in the city. Cuz most of the DJs were buying two copies too because they’re doing beat juggling. So next thing you know, I’m like ‘wow if I do a song in a day and just released a record every month, I could sell a couple thousand. That [could] be my job.’ And that was the mindset. That’s all I cared about was making a hot record for Detroit.”

Soon, however, Jeffries discovered that his record distribution was well beyond local.

“These records I made were strictly a Detroit sound, it’s for Detroit,” he remembers. “That’s all I cared about - I had no clue Record Time was taking my records and selling them to places in Germany, England, everywhere. I was 19 years old when I got asked to play internationally and the first places I played were in Germany and England.”

As ghettotech expanded globally to Europe, people weren’t sure what to think about the genre. “I still remember the first time anyone heard that shit outside of Detroit,” Jeffries chortles. “There were people that were confused but loved it. There were people like ‘this guy’s scratching like a hip hop battle DJ over all this music, like what’s going on here?’ So it was more like a visual show and they were dancing. It was cool, it grabbed a lot of attention but there’s a lot of ‘what’s this sound? I never heard this shit before. This is just crazy.’ “

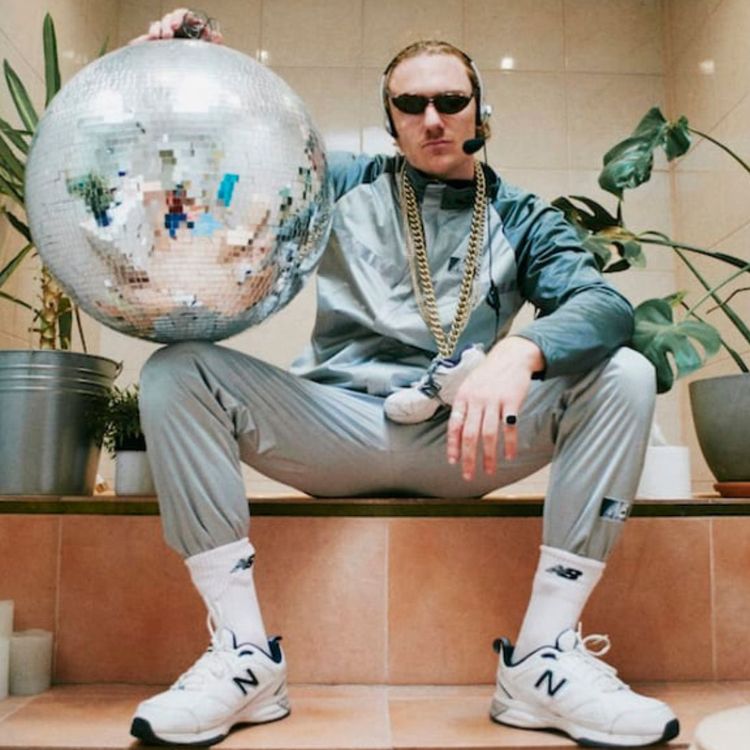

Dj Godfather at Movement Detroit 2022

It wasn’t just the Europeans who were confused by the burgeoning genre, “There were only a few people [making ghettotech], so the first time people heard this thing, everyone was just dumbfounded but they loved it.” Jeffries recalls. “It was refreshing, you know? It was kinda like a basement party version of electronic music. We put the party back in because you had a lot of snobs taking house and techno way too seriously.”

“They still take house and techno way too seriously,” I interrupt. “Yeah,” he laughs. “But that’s still boring as fuck to me.”

You can call ghettotech many things. Boring will never be one of them. And in Jeffries opinion, that’s as it should be, “That’s the whole point of this, you know, it’s the street version of techno. And that’s even how it got its name.”

Jeffries explains the etymology, “You know it got that name from the press, we never even said, ‘Oh let’s come up with a genre and call it ghettotech.’ None of us even named it that.”

The name ghettotech came from a journalist, “His name was Hobey Echlin and he used to write for URB Magazine,” Jeffries recalls of the genre’s labeling. “He was a Detroit native but he lived on the West Coast and he was really into the sound but then he saw this gap where he’s writing on a whole genre of music that no other writers were writing about.”

Even the locals weren’t sure what to call it, “[Echlin] ’s like, ‘Well, I have some people in Detroit, they call it mix music. I ask other people, they call it bass music or they called a Jit music.’ And he’s like, ‘No one has a fucking name for it.’”

Before Echlin coined the term, Jeffries was always very sure of what the music was all about, “I was raised on Miami Bass and I was raised on Detroit techno. Everything I took in, I fused into a sound, and that’s how [ghettotech] came [to be], from my point of view.”

Once the name ghettotech stuck, so did the distorted associations of the genre—the biggest source of contention: the lyrics.

“It was annoying as fuck.” Jeffries laments after I ask about the association ghettotech has with sex-charged lyrics. “People thought ghettotech is just sexually based lyrics and it’s like a sexual thing. And it’s like, you guys are picking one song out of 15 that has like ‘hoes, take off your clothes or ass and titty lyrics. But the next record is an instrumental, And the one after that is talking about jittin’ which is a footwork dance that’s part of the culture. So I always had to straighten out the press, the second they said ‘oh well this sexually..’ I interrupt ‘stop saying that. There’s some…well, there’s a lot, yes. But it’s not what it’s about.”

For Jeffries, “ghettotech is the only genre that has its own culture” not only are the DJs beat-juggling-battle-DJs, but there’s also a culture around the jit battles.

Maybe it was the shady back alley record deals or growing coverage of the media-coined genre, but the lasting legacy of ghettotech is no longer “straight up Detroit shit.” The next generation of ghettotech producers are culturally and regionally diverse, like Australian native Partiboi69 or Berlin-based Mell G. Yet, what we’re seeing is how these international talents are using Detroit ghettotech as a foundation and adding their cultural influences to it.

“It’s just cool because they’re (Partiboi69 and Mell G) influenced by us but taking where they’re from and their attitude and things from their city and they’re mixing those elements with this [Detroit sound].”

Another exciting aspect of ghettotech’s legacy is embracing multi-lingual lyrics, “I mean there’s a whole crew in Brazil doing all this shit too, and the lyrics are in Portuguese.” Jeffries shares. “There are these guys from Paris, and they wanted to use my vocals [for a sample] and I was like, ‘why do you want my vocals? You should do that shit in French. They’ll relate to it a lot better.’”

That’s not to mention some non-English producers attempting to speak the language of Detroit, “They’re are taking Detroit records, with Detroit slang in it and I go, ‘do guys even know what ‘running Bustos is? Why would you sample it? You don’t even know what it is.”

While I’ll spare you the Bustos definition in this article, the point remains: the legacy of ghettotech is no longer exclusively Detroit.

This is an exciting time for new ghettotech creators. For the ones who have been there since the beginning, like Jeffries, it’s even more important to stay true to yourself.

“It’s cool, but that’s another reason why I kind of stick with my old style because I don’t want to sound like what these new guys are doing which is cool, you know, I just want to have my own identity still.”

DJ Godfather has even more music set to be released this year and if you’re lucky enough to live near Detroit, be sure to see the past, present, and future of ghettotech when DJ Godfather and Partyboi69 play at Magic Stick on October 7th.